“In-Group Love” without “Out-Group Hate”

“In-Group Love” without “Out-Group Hate”

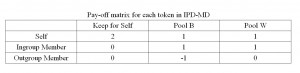

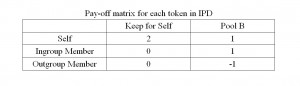

Two types of economic games were introduced: the Intergroup Prisoner’s Dilemma game (IPD) and the Intergroup Prisoner’s Dilemma-Maximizing Difference game (IPD-MD). In the IPD game participants allocated tokens between a pool for themselves and a between-group pool (pool B). In the IPD-MD game participants allocated tokens among a pool for themselves, pool B and a within-group pool (pool W). As shown in the pay-off matrices below, a token allocated in pool B will benefit everyone in the group and harm the other group while a token allocated in pool W will benefit everyone in the group without harming the other group. The optimal strategy for individual would be keeping all tokens for themselves. In the IPD game, the optimal strategy for the group would be putting all tokens in pool B. However, if the other group do the same, both groups will gain nothing. In the IPD-MD game contributing to pool W makes a group gain without intergroup competition, but there is no guarantee the other group would do the same.

1. What They Did – Intervention Summary:

Participants were randomly assigned to two conditions. In the IPD-MD condition participants played IPD-MD game for 60 rounds. In the IPD condition participants played IPD game for 30 rounds and then IPD-MD game for another 30 rounds. All decisions were made in private using a computer. Participants played in a group of 3 against another group of 3. Group composition and group matching were kept constant throughout the study. At the end of the study participants were paid for every points they earned.

2. What They Found – Results:

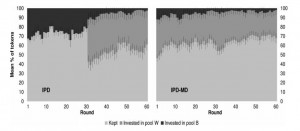

For the IPD-MD condition, as can be seen in the picture below, participants contributed on average 31.54% of their endowment to pool W, as compared with only 5.25% to pool B. The rest of the endowment (63.20%) was kept for private use. For the IPD condition, in the first (IPD) part of the interaction, the rate of contribution to pool B was 26.50%. In the second (IPD-MD) part, despite the competition in the first part, the contribution rate to pool B dropped to 5.72%. The present experiment established that out-group hate does not evolve spontaneously in interaction between randomly composed groups, not even after a period of intergroup conflict.

3. Who Was Studied – Sample:

Undergraduate Students

4. Study Name:

Halevy et al., 2012

5. Citation:

Halevy, N., Weisel, O., & Bornstein, G. (2012). “In‐Group Love” and “Out‐Group Hate” in Repeated Interaction Between Groups. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 25(2), 188-195.

6. Link:

http://www.econ.mpg.de/files/2012/staff/Weisel_JBDM_2011.pdf

7. Intervention categories:

An opportunity to show ingroup love without outgroup hate

8. Sample size:

144

9. Central Reported Statistic:

In the IPD condition, a repeated measure ANOVA with block as a within-subject variable and contribution to pool B as the dependent variable found a highly significant block effect (F(3,33)=25.80, p<.001).