Love thy neighbor: Ingroups, outgroups and collaboration possibilities

Context: Research on intergroup conflict is well supported and grounded in implementing collaboration. However, despite this data, conflict continues to grow and develop. In the present research, Waytz, Young, and Ginges (2014) provide context as to why individuals and their respective group associations may fail to respect peace-promoting findings through an analysis of “motive attribution asymmetry.” Motive attribution symmetry is an assumption-based pattern that involves ingroup vs. outgroup tendencies to respond with either biased ingroup-love or outgroup-hate assumptions.

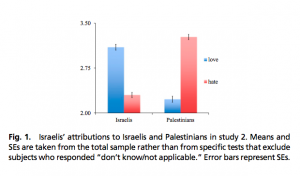

Waytz et al. (2014) hypothesize that people will “attribute ingroup engagement in conflict to love more than hate…. but [also] attribute outgroup engagement in conflict to hate more than love” (p. 15687) Within five separate studies, Waytz et al. (2014) utilize several distinct intergroup conflicts, violent and non-violent, aiming to understand individuals’ innate sense of ingroup and outgroup motives and subsequent intergroup assumptions.

Study 2 and Study 3 outline continuing information found in study one: individuals tend to support the motive attribution asymmetry pattern and generally form internal biases that follow outgorup-hate assumptions and ingroup-love assessments.

Study 5: Incentivizing Accuracy

1. What They Did – Intervention Summary:

The motive attribution symmetry pattern is not only negative (i.e. hate assumptions) but also inhibiting compromise. Waytz et al. wanted to see what may curb its effect and thus improve likelihood of cooperation.

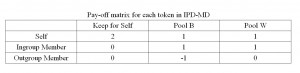

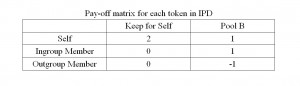

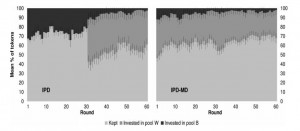

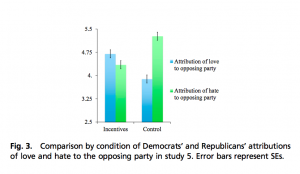

In this study, 331 American democrat and republican residents participated by completing an online study similar to study 1. Those who answered with a secure political ideology were then asked if they felt their party was motivated by various items. Items ranged from love (empathy for others in your own party) to hate (dislike of opposing party members). Participants were then randomly placed into either an incentive experimental group or a control group. Both were told to guess the motivations of the opposing political party, however those in the incentive group were given the notion of earning 12 extra dollars if they estimated correctly. The questions asked were the same asked prior, but now about the opposing party, be it republican or democrat. Lastly, each condition rated how much the would be willing to negotiated with an opposing party.

2. What They Found – Results:

Researchers were excited to find that when provided incentive, the experimental group diminished motivational attributions of hate and increased the motivational attribution of love for outrgroups. Thus, the pattern seen through the motive attribution symmetry in the previous four studies is derailed and actually reversed when individuals are presented incentives. Incentive was found to increase optimism in terms of the conflict, and thus could open doors towards future agreements and compromises.

However, despite this exciting discovery, Waytz et al. suggest that these findings were in a context less violent and volatile than those in other intergroup contexts.

Green – Attribution of hate to opposing party

Blue – Attribution of love to opposing party

3. Who Was Studied – Sample:

331 American democrats and republicans; 223 male, 106 female, 2 unreported

4. Study Name:

Waytz et al., 2014, Study 5

5. Citation:

Waytz, A., Young, L. L., & Ginges, J. (2014). Motive attribution asymmetry for love vs. hate drives intractable conflict. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(44), 15687-15692. doi:10.1073/pnas.1414146111

6. Link:

http://www.pnas.org/content/111/44/15687.abstract

7. Intervention categories:

Intergroup Conflict, Ingroup love, Outgroup hate, Attribution, Cognitive bias, Political ideology, Politics, Republican, Democrat, 2014

8. Sample size:

331

9. Central Reported Statistic:

“Most importantly, a significant condition × target × motive interaction [F(1, 329) = 42.05, P = 0.001, η2P = 0.11] (all other effects, P > 0.39)”