How do Democrats and Republicans view their political opponents? Ken Berwitz and Barry Sinrod investigate this question in The Hopelessly Partisan Guide to American Politics: An Irreverent Look at the Private Lives of Republicans and Democrats, a lighthearted publication examining Democrat and Republicans’ answers to surveys discussing everything from their favorite type of movies to whether they organize the bills in their wallet. The survey reflected that people generally believe the differences between Democrats and Republicans extend beyond their political opinions (for example, most agree that Democrats are more likely to go out on the town on the weekend, and Republicans are more likely to stay in). In fact, previous psychology research has indicated that meaningful and stable disparities in personality do exist across party lines. Conservatives, for instance, tend to score higher on the “conscientiousness” factor of the “Big Five” personality traits (items concerned with self-discipline, organization, and planning), and liberals tend to score higher on “openness to experience” (items indicating an interest in art, emotion, curiosity, and imagination).

A More “Liberal” Room A More “Conservative” Room

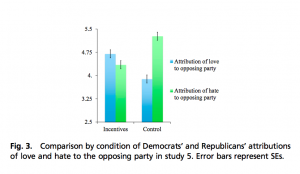

These differences have been explored in research by psychologists Carney, Jost, Gosling, and Potter (2008), who examined the offices and bedrooms of liberals and conservatives for cues to their personality, and found that liberals were indeed more likely to have items in their room indicating an interest in novel experiences and creativity (e.g., books about travel and music, art supplies, international maps), and conservatives items indicating organization and cleanliness (e.g., calendars, laundry baskets, ironing boards). Liberals and conservatives seem to be correct in recognizing that their political counterparts have distinct interests and personality traits. While these perceived differences are relatively innocuous, liberals and conservatives frequently see members of "the other side" as dissimilar in a very negative light. TheHopelessly Partisan survey takes a more somber turn when the authors asked respondents to describe the characteristics of members of the opposite party. The findings, while perhaps not surprising, shed light on challenges to positive bipartisan interaction.

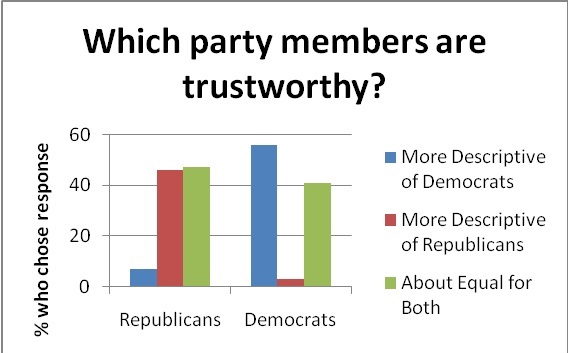

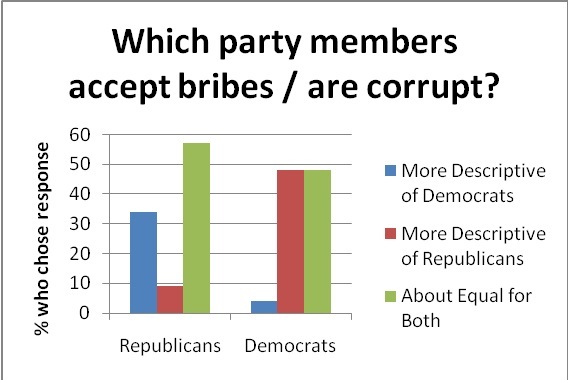

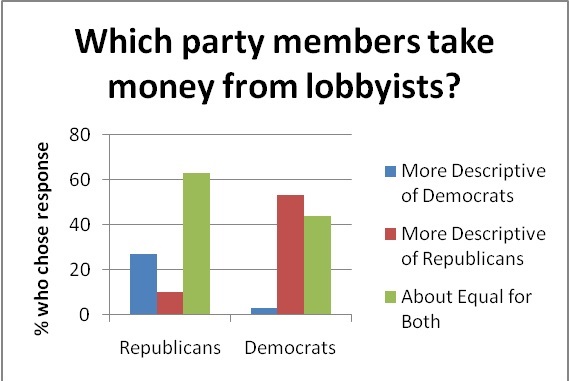

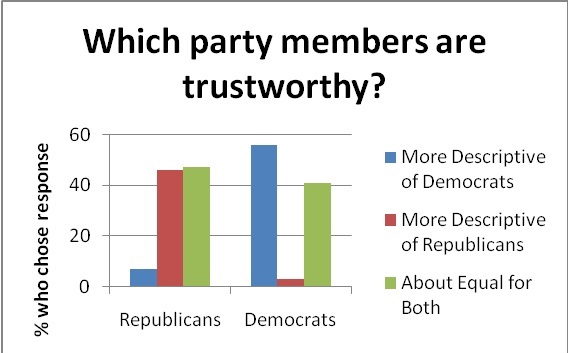

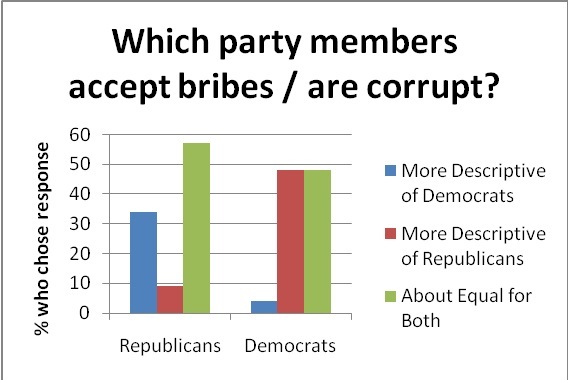

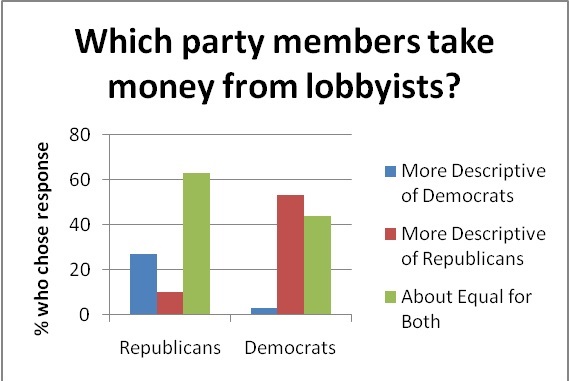

First and foremost, we see that people are rather unwilling to accept their political opponents as well-meaning individuals with cogent beliefs. Out of all of the insults hurled at members of the opposite political party (for instance, Republican “warmongers” and Democratic “freeloaders”), one of the most frequent epithets was “liar.” Dishonesty was heavily attributed to those who disagreed with one's political opinions. Opponents were continually ranked as having suspect motives – for example, they were more likely to be suspected of taking bribes or accepting money from lobbyists.

In these examples, we see further evidence of the “mirror image perception” phenomenon, in which opposing ideologues have nearly identical stereotypes of one another. Corrupt motives are attributed to the side that opposes us; our ideological peers are seen as upright and virtuous.

Why are we so inclined to distrust our political opponents? Individuals are highly motivated to defend important, self-related beliefs. Previous research on the “belief bias” has illustrated the conflict between logic and belief in deductive reasoning: individuals tend to reject arguments that are logical, but with which they disagree, and accept arguments that, albeit flawed, are consonant with their personal beliefs. Through rationalization, people then justify overlooking potentially logical arguments that don’t match one’s own ideas. Furthermore, a source credibility bias can influence our decision making. While we are readily willing to accept an opinion asserted by someone we like and admire, we refute those issued by people or groups we dislike. We can, perhaps, readily justify ignoring an argument by attending instead to the character of the person delivering it. By viewing those who contradict us as unreliable sources, we quell any chance of having to seriously consider their arguments. Discrediting the proponent of undesirable viewpoints could be accomplished quite easily by asserting that the person is deceptive – thus the frequency of “liar” in heated political discourse.

Research on motivated reasoning reveals just how adept people are at dismantling undesirable beliefs as irrational and unreasonable. When information is pertinent to our personal life, it becomes difficult to view it objectively. For example, women who were heavy caffeine drinkers were less likely to be convinced by an article linking caffeine consumption and breast cancer than low caffeine drinkers; in another study, researchers found that these “threatened” individuals described studies showing the dangers of caffeine as less methodologically sound. So, when a highly religious individual encounters statements from someone such as Richard Dawkins, they might be tempted to react violently to invalidate his arugments, dubbing him “two faced,” “fork-tongued,” and a “spineless hypocrite.”

Furthermore, people seek out evidence that confirms what they want to believe rather than rationally assessing all of the available information. When told that extraversion was an especially desirable trait, people generated more memories of instances in their lives where they were extroverted; when told that introversion is preferable, the effect flipped, demonstrating a clear confirmation bias in individuals’ thought processes. Social psychologist Jonathan Haidt discusses how this occurs: When evaluating a statement congruent with our beliefs, we ask ourselves, “Can we believe it?” and require only a minimal amount of plausibility before we accept the argument as valid. On the other hand, when encountering an assertion that challenges our beliefs, we ask ourselves, “Must I believe it?” and need devise only a single crack in its foundation in order to cast it aside. For example, a person inclined to dislike Obama hears that people have had trouble tracking down his birth certificate. They ask, can I believe that Obama is not a natural born citizen?, and see the alleged missing birth certificate as sufficient evidence. On the other hand, when the birth certificate is posted online, potentially refuting these arguments, the person asks, must I believe it?, and instead labels the birth certificate a forgery, as a "short-form" and invalid certificate, and so on. People tend to search for information that supports important, self-referential beliefs, disregarding information that contradicts them. And in the information age, the Internet is ready to provide dozens of “sources” that can offer evidence for any number of theories, from those insisting that planted bombs caused 9/11 to those claiming Obama is the Anti-Christ.

Fortunately, research has indicated that motivated reasoning has its limits. When presented with conflicting information about a candidate in a mock presidential primary that they originally supported (e.g., a pro-choice individual discovered that the candidate was pro-life), people initially responded along the lines of motivated reasoning, increasing their positive attitude towards the candidate and ignoring the contradictory information. On the other hand, as the amount of incongruent information learned grew, people began making adjustments to their evaluations of the candidates, appraising the situation more accurately and taking more time to review the information they were given. Although people are initially predisposed to excuse their politician of choice's faults, they don't appear able to gloss over everything. See, for example, this quote from a once-ardent Obama supporter: "Now after over 6 months in power, after the novelty has worn off, after months of 'Yes We Can!' should have become 'Yes Let's Do It!', we all realize that the person that we supported is really a centrist who plays a Progressive on TV." People can reevaluate and re-frame their beliefs.

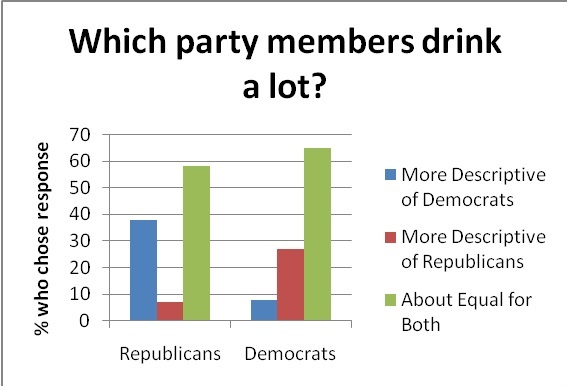

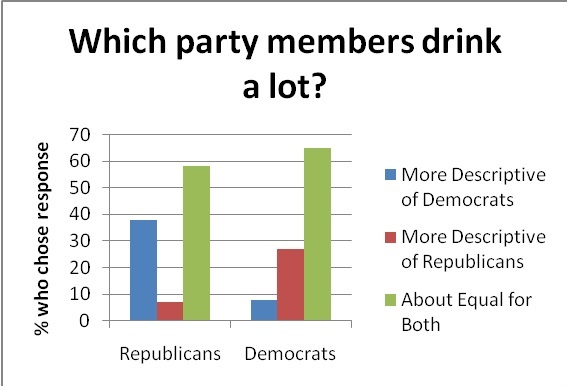

However, as illustrated in The Hopelessly Partisan Guide,aspersions about “the other side” reached far beyond a political context. Democrats and Republicans were willing to attribute all sorts of vices to the others and, in turn, claimed the moral high ground for themselves. For example, Democrats and Republicans asserted that they drink less, enjoy gambling less, and are more tolerant of minorities (Democrats demonstrated an especially marked bias in this case) than their counterparts. In a reverse halo-like effect, partisans attributed all kinds of immoral characteristics beyond mendacity to their opponents.

With this thorough “de-moralification” of our political opponents, it’s not surprising that politicos can hurl such insults at one another, and, in an extreme case, profess not to care if their opponent died in front of them. 95.4% of Americans recently polled asserted that civility is important for a healthy democracy – and many aver that problems of incivility might be solved by cross-party interaction. For example, 85% of Americans surveyed believe that politicians should work to cultivate friendships with members of the opposite party.

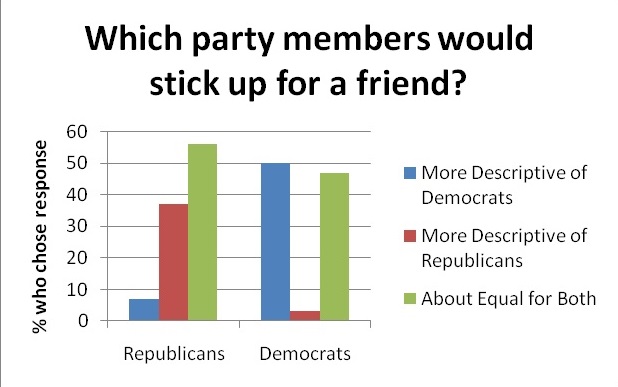

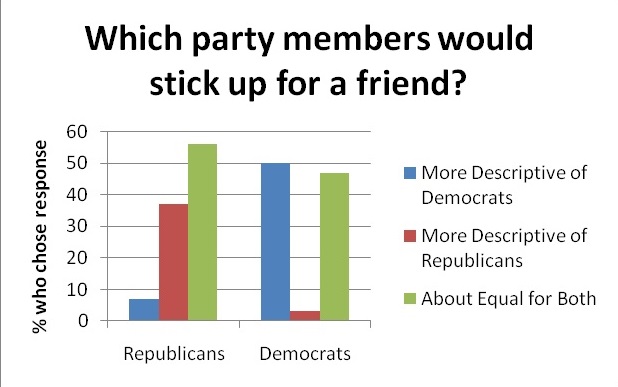

However, it seems some are disinclined to freely associate with political others – Hopelessly Partisan data indicated that people tend to think political kin make better friends.

Psychological research has long validated the notion that “birds of a feather flock together” – rather than opposites attracting, people like those who are attitudinally similar to themselves, and even deem them more moral individuals. Since people might be less inclined to form bipartisan friendships on their own, some assert that the workplace might actually be the best place for cross-cutting political discourse. Self-selection has begun to occur in neighborhoods, churches, and community organizations, as people group themselves with people who are ideologically similar; however, this self-selection generally cannot occur at work. Political scientists Mutz and Mondak (2006) found that dialogue between ideological opponents increased at work, resulted in a greater awareness of rationales for viewpoints other than one’s own, and that there was an association between political tolerance and the number of political discussion partners one had at work. Perhaps, then, public places like the workplace and schools could be used to foster civil interaction. Many Americans echoed this sentiment in a recent survey, with 77% stating that schools should teach respect in politics, and selecting local schools as the best way to promote civil politics.

Is politics hopelessly partisan? Sometimes it might seem so, when even the most well-educated and intellectual individuals instantly label members of the opposite political party as insane and idiotic. However, considering that motivated reasoning doesn't appear to persist in the face of everything, there is hope that judgments of our ideological opponents could also be corrected. Most of the research on reduction of bias and prejudice has focused on race and sexual orientation, but perhaps some of the same techniques could be implemented to assuage cross-party polemics. Given enough examples of well-meaning and reasonable individuals with whom one disagrees, one might be able to view "the other side" with less hostility.

Author Info

Conservative Ken Berwitz is a native New Yorker and the President of Ken Berwitz Marketing Research (KBMR) and National Qualitative Centers, Inc. (NQC). He has been involved in executing, writing, and speaking about qualitative and quantitative research for over 35 years. Liberal Barry Sinrod has conducted surveys in the marketing and research community for nearly 40 years and writes for the Boca Raton News on a weekly basis.

– Lauren Howe