Stewart/Colbert’s Rally to Restore Sanity and the Psychology of Moderates

As someone who is interested in promoting civility and reason in politics, I have been really excited over the past few days by Jon Stewart’s announcement of a Rally to Restore Sanity (“Million Moderate March”), coupled with Stephen Colbert’s satirical “March to Keep Fear Alive”. The below video, where the announcement is made, is well worth watching, if only for it’s entertainment value.

| The Daily Show With Jon Stewart | Mon – Thurs 11p / 10c | |||

| Rally to Restore Sanity | ||||

|

||||

Normally, we look at our yourmorals.org data in terms of liberals and conservatives, but what can we say about moderates. In many instances (e.g. Measures of general moral or political positions using Moral Foundations or Schwartz Values), moderates score between liberals and conservatives. However, there are a couple interesting findings about moderates in our data that might be of interest.

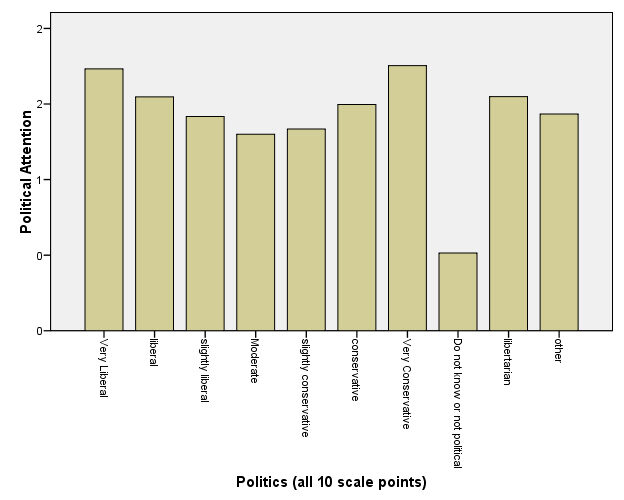

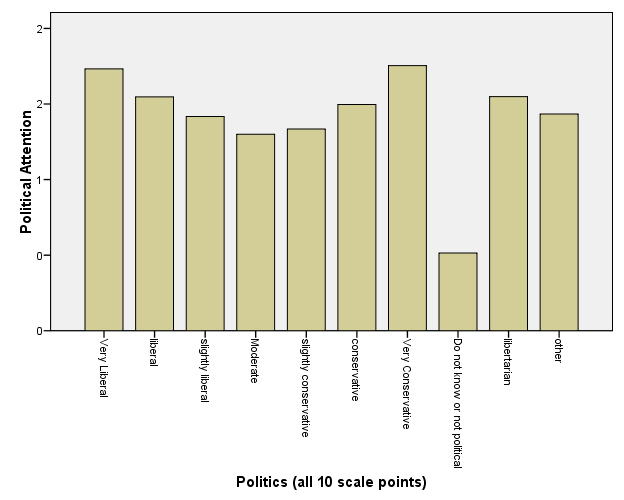

First, moderates are less engaged in politics. This isn’t a particularly controversial finding as research in social psychology shows that extreme attitudes are more resistant to change and more likely to predict behavior. Moderates are defined by their lack of extremity and this lack of extremity predicts a disinterest in politics and lack of desire to engage in political action.

As such, it is not surprising that, as Stewart notes, the only voices which often get heard are the loudest voices. Shouting hurts your throat and moderates are unwilling to pay that price. But couched in terms of entertainment and comedy? Maybe that will spur moderates to attend in a way that an overtly political/partisan event could never do.

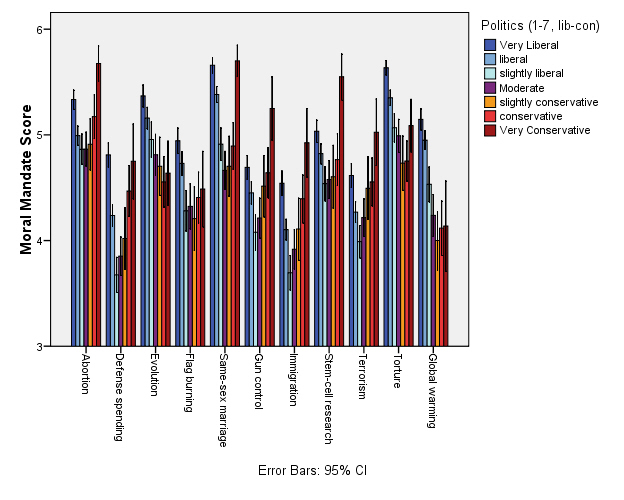

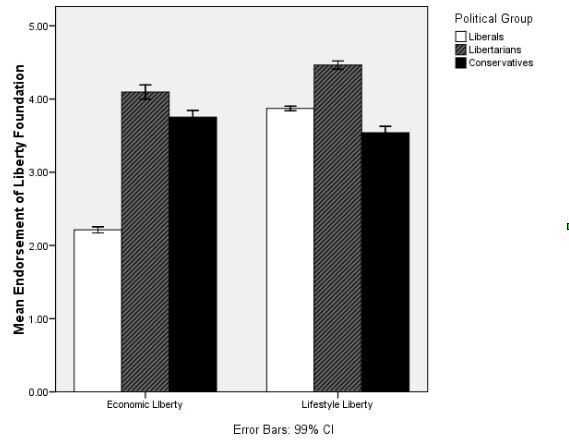

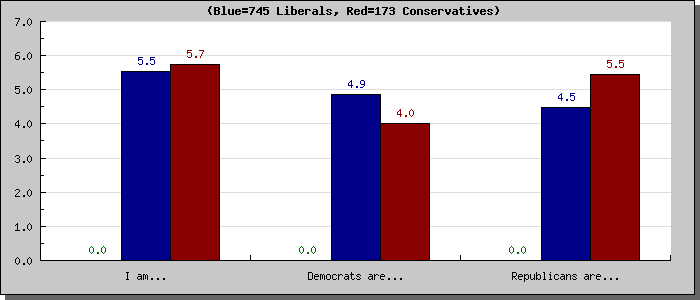

Going a bit deeper, the other area where moderates score differently than liberals and conservatives is in terms of their willingness to moralize issues. Moderates are less likely to frame issues as moral and less likely to be moral maximizers. Morality can be a great force for good, but there is also research on idealistic evil and the dark side of moral conviction. You’ll notice that while liberals and conservatives moralize individual issues in the below graph at different levels, the extremes generally moralize issues more than moderates or less extreme partisans. It’s worth noting I recently attended a talk by Linda Skitka where her team found (in China) that high moralization scores predict willingness to spy on and censor people with opposing viewpoints.

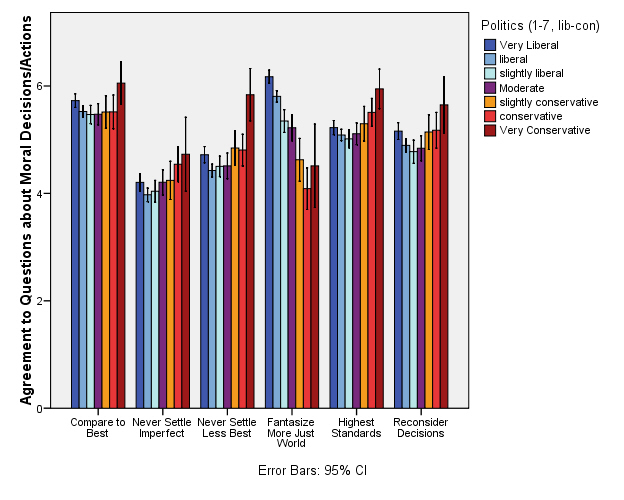

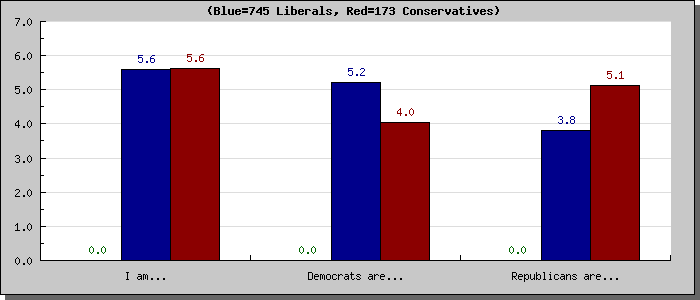

Moderates also score lower on a general (not issue specific) measure of moral maximizing. Below is a graph of scores on individual moral maximizing questions. Again, a lot of good may be done in the name of morality and moral maximizers may be less willing to let people starve or let injustice stand. However, a lot of bad may be done in the name of morality as well and “never settling” for imperfect moral outcomes seems like a recipe for the kind of political ugliness that we see these days. Moderates appear willing to accept imperfection in the moral realm.

Maximizing is a concept made popular by Barry Schwartz at Swarthmore in his book, the Paradox of Choice and his TED talk. The argument isn’t that high standards are a bad thing…but that at some point, there is a level where overly high standards have negative consequences. The point that Stewart and Colbert are making is that perhaps partisans have reached that point in our political dialogue, to the detriment of policy.

I probably won’t make it to DC, but I do plan on celebrating the Rally to Restore Sanity in some way, perhaps at a satellite event. I am generally liberal and will be surrounded mainly (though not exclusively) by liberal friends. It would be really easy to use the event as a time to mock and denigrate the extremity of the other side. However, liberal moral absolutism has it’s dangers too. For those of us who really want to restore sanity to political debate, it is an opportunity to be the change we want to see in the world and take a moment to reflect on how our political side can ‘take it down a notch for America’, rather than assuming that Stewart is talking to ‘them’. And perhaps that begins with accepting some amount of moral imperfection.

– Ravi Iyer