Those who want a fight, like Trump and ISIS, do indeed benefit from each other.

During the recent Democratic debate, Hillary Clinton stated that Donald Trump has become a lead recruiter for ISIS. I can’t speak to the accuracy of this claim, and much has been written from both sides elsewhere. However, there should be very little doubt that those who benefit from conflict need the level of perceived competition to be ever greater, in order to justify their combative stance within their own group, implying that the extremes on both sides of any conflict do indeed have common goals. That is true in social science laboratory experiments, natural experiments that occur in the world, analyses of history, in our everyday experiences and yes, it is true with regard to those who benefit from a perceived “clash of civilizations”, such as Donald Trump and ISIS. Indeed, it would be shocking if it didn’t work that way for Trump and ISIS, as shocking as it would be if gravity worked in some places and not others, as these forces are fundamental parts of human nature. We are naturally social animals who are exceedingly good at forming groups and competing with opposing groups. The more competitive the situation gets, the more animosity arises and the more we gravitate toward the most combative amongst our group.

Need proof? Here are five forms of evidence that suggest this is true.

1) Social Science – Thousands of studies have used the minimal group paradigm, whereby the mere fact of assigning a person to a group creates animosity and the more competitive the groups are, the more animosity ensues. The reason the procedure is called “minimal” is that there is no actual reason why any person is put in any group, such that any reason for conflict is simply a result of random group assignment + competition, not any real difference between individuals. During these manufactured competitions, group members are more likely to follow others who suggest attacking the other group.

2) The Natural Experiment of Sports – How do we know that the minimal group paradigm maps onto real world behavior? Millions of people engage in animosity toward very similar others due to the arbitrary assignment of where they happen to live and what sports team they then follow. Thousands of papers have been written to analyze this behavior (I’d recommend Among the Thugs most), but you don’t need academic analyses to know that rivalries lead to violence across sports and countries, as it happens regularly in the news. Importantly, the only thing that often differentiates these groups is the level of competition between them; the greater the competition, the more animosity, and the more opportunity for heroes to arise, who lead their side to victory.

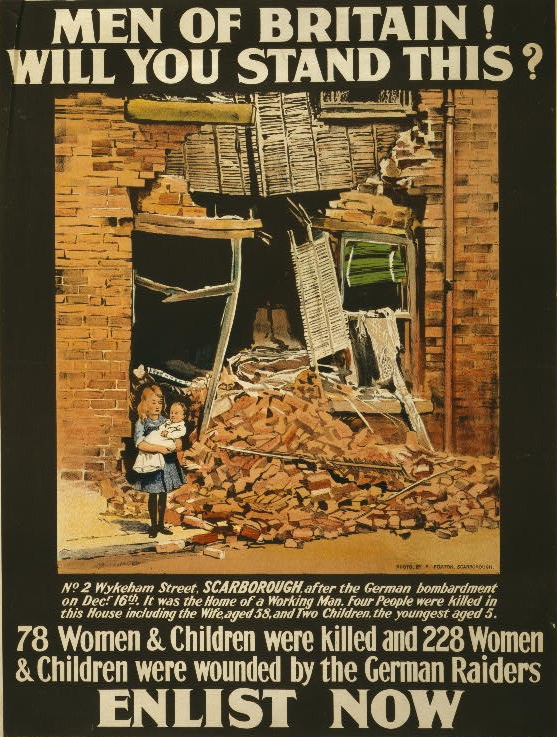

3) History – How do dictators get their populace to follow them, despite their often ineffective leadership? North Korea needs a perpetual sense of threat to justify the terrible conditions it imposes on it’s people. Hitler, Stalin, Pol-Pot, and Putin, in modern times, maintain(ed) their hold on power not by providing a better life for their people, but by “protecting” them from a very dangerous world. The more competition that exists with other countries, the better their hold on power, a phenomenon that has noted by political scientists in the US as well.

4) Everyday experience – A lot of social science and history simply confirms what we already know from our everyday experience. When was the last time that you got into an argument with someone and one party willingly conceded their point of view? The more heated the debate, the less you listen to others, and the fact that social scientists have found this to be true is almost beside the point. Creating a more extreme atmosphere is a great way to shut down reasoned debate and compromise.

5) Trump & ISIS – I don’t doubt Trump’s sincere desire to defeat ISIS, but support for his candidacy has clearly increased as more terrible events occur in the world. Indeed, a prime emphasis of his candidacy is competition with ISIS, China, Mexico, etc, and his proposed toughness in dealing with them. He demonstrates this toughness by being ever more extreme. Similarly, while systematic analyses of terrorist attitudes are sparse, groups like ISIS have often arisen in response to perceived invasions of Islamic territory such as in the Middle East or Afghanistan, and a prime emphasis of ISIS’ propaganda is over-the-top shock videos designed to display toughness, in the face of these threats.

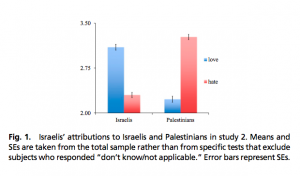

In the end, human beings will rally to a “tough leader” when under threat. Intentional or not, those who demonstrate their toughness through their extreme rhetoric, often benefit from this threat, leading those on either extreme side of any moral division to be strangely aligned in terms of their incentives. Trump & ISIS’ relationship is similar to the relationship between Democrats and Republicans who fundraise off of the extreme words of the opposing side or the Ohio State and Michigan athletic departments, who each earn millions from their rivalry or Hamas and the current conservative Israeli government, who both gain in popularity based on each others’ more extreme actions, or east coast and west coast rappers, whose rivalry led to millions in album sales. Human beings love competition and often, those who promote the competition amongst us reap the rewards. Unfortunately, some of these competitions have enduring consequences and there are times when those of us who would prefer to build bridges rather than walls need to get psychology working for us, rather than against us.

– Ravi Iyer