More Information does not necessarily lead to Civility

A recent article by Ezra Klein at Vox.com eloquently makes an argument that we at CivilPolitics have also done a lot of research in support of – specifically, that if you want to affect many behaviors, you cannot just appeal to individuals’ sense of reason. The article is well worth a complete read and is excerpted below, but the gist of it details a simple clear study by Dan Kahan and colleagues, showing that individuals who are good at math stop using their rational skills when the use of those skills would threaten their values.

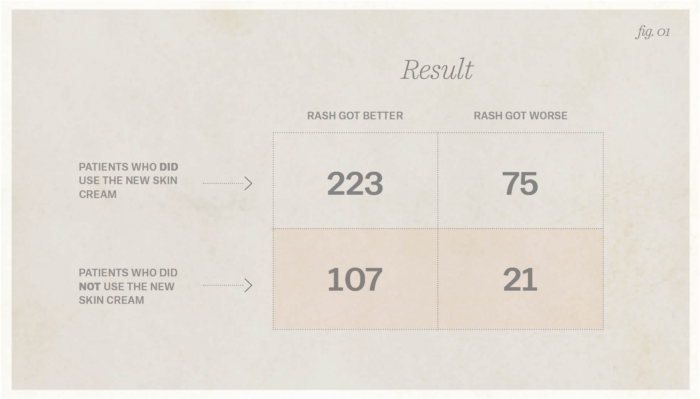

How was this shown? Consider the below table of results of a hypothetical study on whether a skin cream helps individuals with a rash. Did the skin cream work well? Simply scanning the numbers may give you the impression that the skin cream did well, as 225 is the highest number in the chart, yet if you look closer at the numbers, you’d find that the use of the skin cream is actually more likely to do harm than good, when compared to not doing anything at all. However this kind of logical reasoning takes effort.

Kahan’s work shows that we aren’t willing to make this kind of effort when the results would conflict with our values. Specifically, when confronted with a ideologically charged political question (e.g. gun control) framed in the same terms, individual skill at math no longer predicts being good at solving such a problem . Instead, one’s ideology was the main predictor and this was true for both liberals and conservatives. From the article:

Presented with this problem a funny thing happened: how good subjects were at math stopped predicting how well they did on the test. Now it was ideology that drove the answers. Liberals were extremely good at solving the problem when doing so proved that gun-control legislation reduced crime. But when presented with the version of the problem that suggested gun control had failed, their math skills stopped mattering. They tended to get the problem wrong no matter how good they were at math. Conservatives exhibited the same pattern — just in reverse.

Being better at math didn’t just fail to help partisans converge on the right answer. It actually drove them further apart. Partisans with weak math skills were 25 percentage points likelier to get the answer right when it fit their ideology. Partisans with strong math skills were 45 percentage points likelier to get the answer right when it fit their ideology. The smarter the person is, the dumber politics can make them.

Consider how utterly insane that is: being better at math made partisans less likely to solve the problem correctly when solving the problem correctly meant betraying their political instincts. People weren’t reasoning to get the right answer; they were reasoning to get the answer that they wanted to be right.

If more information is not the solution to producing civility, than what is? Our expertise at Civil Politics.org is in social psychology, which often concerns the subtle influences that can affect our non-rational side. While we are still working on a comprehensive set of recommendations (check our blog for continuing progress and research), our social psychology page details a few simple principles that one can use in addition to providing information. Specifically, getting people to like each other more can make them more open to opposing arguments. Providing a non-oppositional framework also creates space that allows for more civil thoughts. These themes also run through the work of organizations we work with, such as Living Room Conversations and The Village Square, which, consciously or not, effectively use social psychological principles in their work. Whether you are more convinced by research in the lab, case studies, or a combination, the evidence is clear – more information, by itself, will not bring groups closer together. To do so requires considering the many emotional and psychological motivations that we all have.

– Ravi Iyer

Benkarkis 10 years ago

It’s all about emotion in the end. You can mask it in so called facts. Perception rules.