Self-Affirmation: The Key to Communication

1. What They Did – Summary:

This study, primarily focused on effects of self-affirmation in the face of counterarguments and values, solely recruited participants who identified as “patriots.” Within a 2×2 study design, the patriots were placed into one of two separate conditions: a convictions salient condition and a rationality salient conviction. Both groups began by completing the beginning of a questionnaire entitled “Study on Personal Characteristics and Life Domains” in which they ranked a list of “personal characteristics and life domains” in terms of importance to their personal lives.

Next the comparison of affirmation vs. threat to ones identity or self was administered. Within the affirmation condition, the participants wrote down a memory or experience in which they felt their number one ranked “personal characteristic” (from the previously ranked list) was salient and why such a characteristic is considered most important to them. Comparatively the threat condition retold a similar experience in which they unsuccessfully respected or failed to live up to their number one ranked “personal characteristic.”

Next the participants in both the affirmation and threat conditions were given rational vs. conviction salient questionnaires. Both sides were given claims of either rationality or conviction respectively, on which the participants had to self-report a level of agreement. (ex. “At least once in a while, I try to stand up for my values.”) After said questionnaire, the final portion of the study was administered through a fabricated, politically charged document describing terrorist groups arguing in favor of the rationality of the attacks of September 11th. Reactions were asked of each of the patriots.

Researchers hope to find an interaction between the self-affirming prior exercises and openness to an opposed view of a politically charged topic. (Additional questions throughout the study such as attention to the reading, validity of the answers given and ones self-reported mood during the experiment were asked to understand potential biases in the data.)

2. What They Found – Results:

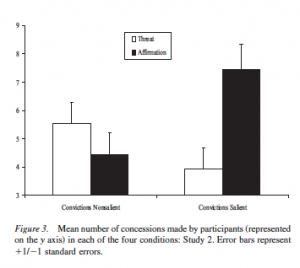

Sure enough, researchers found a statistically significant interaction between the conviction salience and affirmation conditions. The “patriots” who were given the affirming prompts as well as conviction prompts were much more likely to accept or review the politically dissimilar article in higher regard than the comparison group. Moreover, threatened and conviction based “patriots” were less open to accepting the article. Such an interaction was not seen between the rationality salient “patriots”, affirming or threatened.

Ultimately, researchers were able to present data supporting self-affirmation as a means to increased openness to opposing ideas and values, a big step towards improving negotiations and communication.

3. Who Was Studied – Sample:

43 total students: 21 male, 22 female.

4. Study Name:

Cohen et al. 2007, Study 2

5. Citation:

Cohen, Geoffery L., David K. Sherman, Anthony Bastardi, Lillian Hsu, Michelle McGoey, and Lee Ross. “Bridging the Partisan Divide: Self-Affirmation Reduces Ideological Closed-Mindedness and Inflexibility in Negotiation.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 93.3 (2007): 422-24. Ed.stanford.edu. Stanford University. Web.

6. Link:

https://ed.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/bridging_divides1.pdf.

7. Intervention categories:

perspective, self-affirmation, negotiation, MTurk

8. Sample size:

43

9. Central Reported Statistic:

“The predicted, Salience X Affirmation interaction was revealed, F(1, 38) = 4.62, p = 0.38, MSE = 120.”

“The combination of affirmation and heightened salience of personal convictions promoted relatively less negativity and more balance in thoughts and feelings directed at the communication…. prompt[ing] greater recognition of the importance of the persuasive issue.