The Big Sort: When Personal Preferences Build Political Partisanship

"The Big Sort isn't primarily a political phenomenon. It is the way Americans have chosen to live, an unconscious decision to cluster in communities of like-mindedness"

At a recent dinner party, while discussing potential neighbors soon to move into a nearby house, one of the attendees exclaimed, "As long as they are hip, cool, and liberal, I'll be good." Initially, one might be caught off guard by such an utterance – it seems strange for "liberal" to be included within this string of requirements. Why should someone focus so deliberately on the personal politics of their neighbors? However, as Bill Bishop explains in his text The Big Sort: Why the Clustering of Like-Minded America Is Tearing Us Apart, this woman was merely voicing what is tacitly occurring throughout the United States. Bishop investigates "the Big Sort," tracking patterns of migration that reveal that Americans have, over the past three decades, been increasingly sorting themselves into communities where people share the same lifestyle.

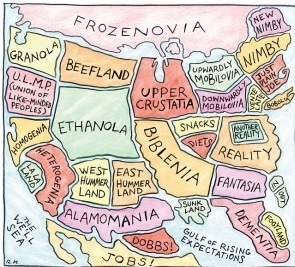

People's concerns while planning a move include the search for "blue cities" or "conservative communities with traditional values." Given increasing freedom and economic prosperity, people choose to move to places where they feel most comfortable and group with similar others, resulting in the creation of homogeneous, geographically distinct pockets. Political alignment has additionally become a part of these lifestyle choices – Democrats and Republicans regularly and systematically differ not only in their party preference, but in their income, education, race, location, and way of life.

Application to Civil Politics

As geography becomes the most significant predictor of political orientation and liberals and conservatives become concentrated in separate communities, cross-party interaction is whittled down to a minimum, minimizing opportunities for civil discussion that might help to foster political tolerance. The Big Sort is, according to Bishop's findings, responsible for political imbalances that grow more and more pronounced each year. The end result of this mass movement are "balkanized communities whose inhabitants find other Americans to be culturally incomprehensible; a growing intolerance for political differences that has made national consensus impossible; and politics so polarized that Congress is stymied and elections are no longer just contests over politics, but bitter choices between ways of life."

The Big Sort reveals one of the causes of the current, polarized political climate, explaining why people are simply unable to understand, tolerate or respect other political views – their lives are compleltely focused around and are surrounded by a singular mindset. This is why relations between different political and religious groups can become especially hostile, and why people are so nonplussed when someone from the opposite party is elected (see Matt Motyl’s comment on “I don’t know how [Bush/Obama] won, I don’t know a soul who voted for him” and discussion of group polarization). We mostly associate with those who are “like us,” resulting in a segregation of ideas and increased polarization throughout the United States.

Detailed Chapter Summaries

Introduction

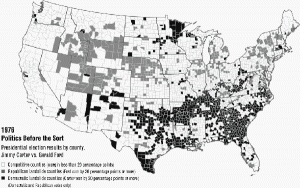

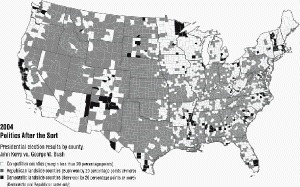

The text opens with Bishop offering an example of the idea segregation he discusses: he and his wife subconsciously moved into a nearly all-Democrat neighborhood because it "felt right," and his neighbors later shunted the opinions of the one local conservative, demanding that he not talk politics with them. Bishop then explains how he stumbled upon the "Big Sort": tracking migration patterns in the United States, initially to determine why some areas were economically blossoming and others stagnant, Bishop and his colleagues discovered that more and more people were living in counties that were "landslide" (where one candidate won by 20 percentage points or more). A closer look revealed that people were moving in order to live with those who share their values, beliefs, and ways of life – they were "clustering in communities of like-mindedness," the consequences of which include an inability to understand even those they live only a few miles away, and an exclusion of those who do not fit the mold, such as Bishop's "lone conservative."

Part 1: The Power of Place

Chapter 1: The Age of Political Segregation

Bishop writes about the discomfort and dangers associated with being identified as a "political outcast" – the burning of campaign yard signs, vandalism, even arguments resulting in gunfire.

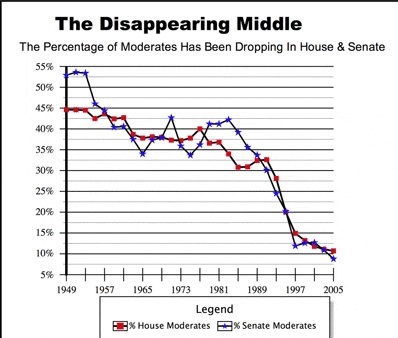

People can intuitively discern what a place's politics are, and thus (generally subconsciously) decide to migrate to places that match their personal politics in the same way they choose which political party to follow: because it "feels right." As the American public began sorting themselves into politically homogeneous communities, elected officials began to polarize, overlapping on several issues in the 1970's, and on almost none by 2002. By 2005, the "moderate middle" had almost evaporated, and only 8% of the House described themselves as moderate, dropping by almost 30% since the mid-1970's. Contrary to some scholars' assertions that only the elected officials, and not the American public, were polarized, ideological allegiances such as "pro-choice" or "pro-life," and for or against the war in Iraq, revealed that those taking a moderate position had declined drastically.

Purported explanations for increasing partisanship included gerrymandering and conservative conspiracy to split the country ideologically by advancing their point of view. However, a look at the data on redistricting revealed that districts grew more partisan in years where there was no change in boundaries, and Bishop argues that conservatives did not create partisanship, but instead recognized existing trends. Rather than being caused by politicians, partisanship is a reflection of real differences in the way Americans live: their decision to surround themselves with similar thinkers.

In the mid-1970's, a particularly bipartisan period, the differences between party members were muted; there was no conspicuous link between conservatism and religious attendance, and women didn't tend to vote Democratic. Shortly afterward, this flipped, and ideology began to reign. As old political, social, religious, and cultural systems of order began to decay, people began to organize their lives around their individual preferences. So, even as the nation grows more diverse, our neighborhoods and the people with whom we interact become more homogeneous and reinforce our existing beliefs.

Chapter 2: The Politics of Migration

More and more counties began to vote consistently for candidates of one party, and, as time went on, the party's candidates would win by larger point spreads, and grew more partisan (this was especially marked in Republican counties). Additionally, people who left Republican counties were much more likely to move to other Republican counties, and the same pattern held for Democrats, while members of the opposing party filtered out. Every region of the United States became less competitive in elections and more partisan. Geography became a better predictor of political opinions (e.g., whether or not a person supported the war in Iraq) than age, gender, occupation, or even religion.

The demographic composition of Republican and Democratic counties was additionally distinct, with Democratic landslide counties having a lower birthrate, and being populated by more well-educated, more foreign-born, more racially diverse, and less religious inhabitants.

Chapter 3: The Psychology of the Tribe

In the early 19th century, politicos who came to Washington, D.C. lived, ate, and voted along with their political brethren. Political segregation pervaded through every aspect of their daily lives, and those who voted against their peers were chastised. This lifestyle altered as people began to move with their families to Washington, and no longer lived in the boarding houses typical of early D.C. This kind of life has, however, again returned to Washington, as politicians no longer bring their families to the capitol, but fly in and interact only with ideological kin.

Bishop discusses psychology research that demonstrated the "risky shift phenomenon," or how groups tend to make more extreme decisions than individuals, including James Stoner's (1961) chess tournament experiment. This shift is especially pronounced in homogeneous groups. The main message: mixed company moderates, like-minded company polarizes. One of the key insights of the founding fathers was that heterogeneity fostered creativity and problem-solving; the clashing of ideas was encouraged. Without this "clashing," partisanship dominates. People vote, but voting becomes less of an expression of political opinion, and more of a sign of group allegiance. Without knowing any actual members of the opposite party, perceptions of the "other side" become more radical and less accurate.

Bishop then discusses the confirmation bias and the tendency for people to confirm their existing beliefs. People choose to listen to news sources that match their preferences and build confidence in their preexisting opinions. This results in partisan individuals reinforcing their more extreme beliefs, and the separation between groups grows larger.

Part 2: The Silent Revolution

Chapter 4: Culture Shift

In the 1950's, Americans were more concerned about political apathy than partisanship. Alliance with a particular party was based less on ideology than on tradition, and only 1/3 of voters could differentiate between the two parties on important issues. Politics were not defined on moral terms, and cross-party interaction was frequent. This was, perhaps, the most bipartisan period in history. In fact, there was a call for more ideologically distinct parties and increased partisanship.

In 1965, everything changed. People abandoned their traditional political and religious affiliations. This can be explained as a result of a culture shift in Americans to "post-materialism," in which, after having basic needs fulfilled and more freedom because of economic prosperity, a change in values takes place, and established institutions are abandoned and mistrusted. Issues of self-expression take precedence over materialism, traditional forms of political participation are eschewed in favor of boycotts, protests, and petitions, and people begin to define themselves by their values. And indeed, starting in 1965, faith in the federal government began to wane to an all-time low (see Jimmy Carter's "malaise" speech). With this lack of trust, politicians were no longer able to accomplish feats like Johnson's War on Poverty, and this trust in government has not returned since then. Post-materialism drastically altered the shape of politics in the United States, emphasizing personal taste and worldview over tradition, religion, class, and occupation.

Chapter 5: The Beginning of the Division

This new, post-materialist politics first appeared in West Virginia around 1974, in a fight over "anti-American" and "anti-religious" textbooks adopted by the school board. The division between the people for and against the textbooks was a division in their way of life, a division based on religion and values.

Furthermore, this division could be seen in geography – the pro-textbook citizens were mostly from Charleston, and the anti-textbook citizens from more rural areas. The groups were furthermore different in their income and education levels, and where they worshiped.

Religion was not always intertwined with politics – in fact, in 1960, 60% of evangelical Protestants were Democrats (compare this to today's statistics). However, starting in the 1960's, groups such as Libertarians and fundamentalist Christians became bound together in a new conservative movement, all favoring restricted government. The "New Right" began to adopt members of the anti-textbook group and similar others, and a religious and political network began to form.

At this same time, traditional voting patterns were reversed. Lower socioeconomic status had previously indicated a tendency to vote Democratic; this trend began to flip. However, as the Kanawha County textbook controversy revealed, divisions between groups were no longer based strictly on income, but rather geography (rural vs. urban), education (college degree vs. working class), and religion (Public vs. Private Protestantism). These divisions frame the conflict in our politics today.

Chapter 6: The Economics of the Big Sort

By the end of the 21st century, the country had separated in a multitude of ways. Well-educated individuals congregated in certain cities, helping the economies there to flourish and increasing the average wages. Whites left factory cities (e.g., Cleveland, Detroit) and the largest cities (e.g., New York, Los Angeles, Philadelphia) and moved into "high-tech" (e.g., Atlanta, Seattle) and recreational/retirement cities (e.g., Las Vegas, Orlando). Blacks moved to cities with strong black communities. Younger individuals relocated to cities with the most technology and highest levels of patent production. Members of the new "creative class" (e.g., artists, engineers, teachers) moved into cities with high rates of patent production. Furthermore, these "high-tech" cities had different characteristics than "low-tech" cities. Interestingly, low-tech cities were more civic-minded, with higher rates of volunteering and more of an emphasis on family values. Part of the reason why these high-tech cities may have been more productive is precisely that there tended to be a lack of strong ties there – and research has demonstrated that weak ties are key to the exchange of ideas. High-tech cities further tend to vote Democratic. All of this is evidence of people sorting themselves based on education, income, race, and how they want to live.

Part 3: The Way We Live Today

Chapter 7: Religion

The success of megachurches is their appeal to like-mindedness, an approach that was suggested by missionary Donald McGavran. McGavran noticed that Christian missionaries were most successful when members of the community began to convince their friends, families, and neighbors to convert. People trust those with whom they have social ties. Many megachurches, for example, are comprised of smaller groups that meet with a common purpose: newly single parents, over 40's, twentysomethings. As people abandoned mainline Protestant denominations, churches were designed specifically to appeal to demographic types. Megachurches were able to recruit such large numbers because they recognized that people were gathering in similar groups, and created churches that fit each neighborhood. Churches have become built around similar lifestyles; the "clash of ideas" has here been eliminated. Republican evangelicals cluster together on Sunday, while liberals gather at Unitarian churches.

Chapter 8: Advertising

A New Trend of "Eco-Advertising"

The principles of national advertising and mass marketing began to be applied to political candidates' campaigns. Advertising began to promote "social-class identification" through products; stores, for example, were encouraged to develop "personalities" targeting specific groups based on their attitudes, motivations, and values instead of demographic characteristics. Marketing research began to focus on appealing to – and even creating (think of Pepsi's "Pepsi Generation") – homogeneous segments of the population. However, this segmentation was not a result of consumer manipulation by the advertising industry; on the other hand, it is a further example of institutions recognizing Americans' movement into homogeneous groups. Interestingly, sales representatives are most successful when making a pitch to a member of the same political party. As common ground was abandoned in the realm of advertising, political campaigns similarly discontinued any attempts to convert Democrats to Republicans or vice versa; instead, campaigns appeal to party loyalty. There are no attempts to build national consensus.

Chapter 9: Lifestyle

People seek out places that best fit their ways of life, values, and politics. Cities have their own lifestyle to offer: Portland, for example, has great public transportation and bookstores that attract liberals; Albuquerque offers Bible study groups and universities that teach creation science, which in turn attracts a different demographic. Throughout the 1990's, people began to move to areas that offered the amenities and lifestyle they desired. For instance, Republicans began to move into places where people lived further apart, fed up with "urban life." Democrats moved into the cities. By sorting themselves according to lifestyle, people also began to sort by political party.

Democrats and Republicans, according to research by political scientists Marc Hetherington and Jonathan Weiler, not only disagree on ideological issues such as abortion and gun control, but also on fundamental issues such as child-rearing. Republicans tend to favor a "strict father" paradigm, emphasizing respect, obedience, and being well behaved. Democrats, on the other hand, act more like "nurturant parents": they stress independence, curiosity, self-reliance, and empathy. Whereas "strict fathers" and "nurturant parents" could once be found across political parties, people's answers to this issue are now a stronger predictor of their party affiliation than income.

People seek out living arrangements that don't challenge their cultural expectations. For example, thematic dorms offer housing specifically for people interested in public affairs, who are concerned for the environment, who like foreign films and art, and so on and so forth. Subdivisions feature sections for Christians and cultural creatives.

Even how people have families became tied up with politics: Democrats marry and have children later, if at all.

Part 4: The Politics of People Like Us

Chapter 10: Choosing a Side

In the mid-1960's, membership in civic organizations such as the AFL-CIO and American Legion declined precipitously. Whereas these organizations were broad-based, cross-class, and encouraged fraternization, the groups that rose in their place advanced narrower, ideological views, and were for advocacy, not socialization. Again, this was a not a left- or right-wing conspiracy; these groups merely reflected existing fractions. And, for every conservative think-tank or foundation that materialized, the left soon had a parallel – the Discovery Institute was the conservative model of the National Center for Science Education; the ACLU was matched by the American Center for Law and Justice.

Democrats and Republicans differ on more and more issues. Differences in cultural opinions are layered on top of older disagreements about economics. Party members are furthermore expected to align with a plethora of viewpoints advanced by their parties; almost every new issue is divided between the parties. Republicans support Wal-Mart; Democrats don't. Democrats condemned the federal reaction to Hurricane Katrina; Republicans found it largely sufficient. Indeed, it seems hardly lucrative as a politician to disagree with one's party members on important issues – Sheila Kiscaden, for example, was elbowed out by the Republican Party for her unorthodox views. There can be no such thing as liberal Republicans – just contemptible "Republicans-in-name-only (RINOs)."

The parties come to represent lifestyles, each offering their own and distinct version. More and more evidence is found that Democrats and Republicans see the world differently. With this deep division at the federal level, state legislatures have begun to settle issues such as abortion, gay marriage, gun control, education, and environmental concerns at a local level instead (e.g., blue states have fewer restrictions on the "morning after" pill, red states have more). People merely move where the laws fit their preferences.

Meanwhile, the percent of moderates in Congress has been declining steadily. This lack of moderates makes it more difficult for Congress to pass legislation. Instead of being productive, each side spends most of their time blaming the other for current problems.

Chapter 11: The Big Sort Campaign

Bishop mentions how the 2004 exit pollsters overestimated the chance of Kerry winning – not because of any faulty polling, but because Bush supporters were more likely to subconsciously avoid talking to younger interviewers, especially those who held college degrees. People avoid talking to those who they believe have different political views from them. According to Bishop, this election was the first during which politicians adopted techniques fitting to "the Big Sort." Democrats and Republicans barely noticed the other side's campaigns, and in the end, the Bush campaign was more successful because it targeted potential voters in the same way as advertising did. The campaign first determined who was likely to be a Republican, and then focused on increasing voter turnout among these individuals. In order to up turnout, they hired massive numbers of young adults to campaign door-to-door, and made sure that these individuals were similar and closely tied to the neighborhoods in which they would be operating – members of the same "tribe" (see McGavran's strategy above). The extensive social networks fostered in typically Republican organizations, such as churches, made this strategy extremely successful.

Further evidence of the Big Sort's influence was evinced in this election: the rural and urban divide between Republicans and Democrats was larger than ever, people split their tickets between parties at an extremely low rate, and Republicans and Democrats disagreed on all of the issues presented to them in a poll – only 10% of voters fell in the middle.

Chapter 12: To Marry Your Enemies

As it currently stands, politics encourages voter isolation and demonizing the other side. Merely bringing different groups together, however, does not instantly foster mutual respect (see, for example, the Robber's Cave study). When the groups have a common purpose, cooperation does increase, and prejudice and conflict are reduced. However, rational political discussion can often still lead to group polarization.

Bishop presents the "emerging church" as the opposite of a megachurch – its congregations are small, questions and doubt are encouraged, and the company is decidedly mixed. The idea is to share life, and live together despite recognizing that other people are different. This questioning attitude transfers to such churches' political standpoints. However, the downside of questioning and doubt is frequently withdrawal and apathy. Partisanship, in fact, increases political participation. How beneficial this increased participation is to democracy, however, is debatable.

The text concludes with an example of cooperation drawn from anthropology. Among the Nuer people, marriage rules encourage widespread alliances and friendship. A common adage is "They are our enemies; we marry them." No such ties between "enemies" are forged in politics today. In the past, partisanship in the United States has been rectified through cross-cutting issues – but the Big Sort is not partisanship merely in political opinion, but so many other aspects of life. As American society becomes more and more fragmented, is there a way to revitalize the phrase e pluribus unum? Or is the vision of a shared way of life borne through compromise obsolete?

Author Info

Bill Bishop lives in Austin, Texas. He wrote The Big Sort with retired University of Texas sociologist Robert G. Cushing. Bishop has worked as a reporter at The Mountain Eagle, in Whitesburg (Ky.); a columnist at the Lexington (Ky.) Herald-Leader and on the special projects staff of the Austin (Tx.) American-Statesman. Bishop and his wife, Julie Ardery, owned and operated The Bastrop County Times, a weekly newspaper in Smithville, Texas. They now co-edit The Daily Yonder, a web-based publication (dailyyonder.com) covering rural America.

– Lauren Howe