Pew Research highlights Social, Political and Moral Polarization among Partisans, but more people are still Moderates

A recent research study by Pew highlights societal trends that have a lot of people worried about the future of our country. While many people have highlighted the political polarization that exists and others have pointed to the social and psychological trends underlying that polarization, Pew’s research report is unique for the scope of findings across political, social, and moral attitudes. Some of the highlights of the report include:

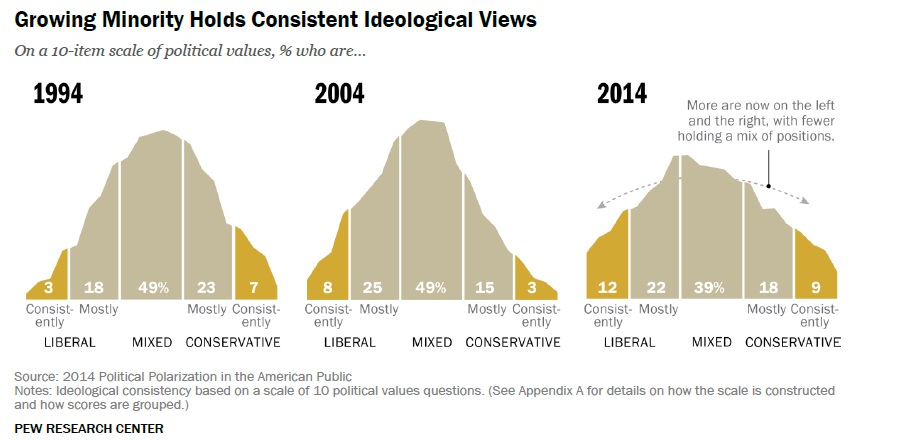

- Based on a scale of 10 political attitude questions, such as a binary choice between the statements “Government is almost always wasteful and inefficient” and “Government often does a better job than people give it credit for”, the median Democrat and median Republicans’ attitudes are further apart than 2004 and 1994.

- On the above ideological survey, fewer people, whether Democrat, Republican, or independent, are in the middle compared to 1994 and 2004. Though it is still worth noting that a plurality, 39% are in the middle fifth of the survey.

- More people on each side see the opposing group as a “threat to the nation’s well being”.

- Those on the extreme left or on the extreme right are on the ideological survey are more likely to have close friends with and live in a community with people who agree with them.

The study is an important snapshot of current society and clearly illustrates that polarization is getting worse, with the social and moral consequences that moral psychology research would predict when attitudes become moralized. That being said, I think it is important not to lose sight of the below graph from their study.

Specifically, while there certainly is a trend toward moralization and partisanship, the majority of people are in the middle of the above distributions of political attitudes and hold mixed opinions about political attitudes. It is important that those of us who study polarization don’t exacerbate perceived differences, as research has shown that perceptions of differences can become reality. Most Americans (79%!) still fall somewhere between having consistently liberal and consistently conservative attitudes on political issues, according to Pew’s research. And even amongst those on the ends of this spectrum, 37% of conservatives and 51% of liberals have close friends who disagree with them. Compromise between parties is still the preference of most of the electorate. If those of us who hold a mixed set of attitudes can indeed make our views more prominent, thereby reducing the salience of group boundaries, research would suggest that this would indeed mitigate this alarming trend toward social, moral, and political polarization.

– Ravi Iyer

Scott Wagner 10 years ago

Thank you for making the point that there are still a lot of us in that middle quintile; it’s an important contribution to the poll’s good press and convincing evidence about both increased polarization and polarization symmetry across ideologies. And I agree that that middle bulge of moderates is still a pretty heavy sumo wrestler to knock out of the ring, even now.

One overlooked dimension may be that every bit of the percentages of Americans at the fringes came at the expense of the middle quintile (~10% change). I find it very interesting that the total percentage of less-fringe partisans didn’t budge at all, even though we can probably safely assume that most of those new extremists came from those somewhat partisan quintiles. Increases in partisanship all the way across the 4 quintiles of partisanship didn’t happen. The data makes for an illusion that all the increase at the fringes actually came from centrists who just hopped over mild partisanship to the fringes. To me, that kind of heterogeneity indicates a dual dimension to the data. Maybe something of what we’re seeing is not well-characterized as the increase in the fringes, but also as a significant loss of ‘centrists’ that want to offset them. In other words, the environment has not only created extremists out of partisans; it has also persuaded about 20% of the center quintile to become partisan for the first time. Those two things are arguably different social psychology processes.

Losing 20% of one’s quintile (from 49% to 39%) is a very fast drain rate. In a very real sense, our potential customers have been leaving us. What are the implications about our national commitment to political moderation? For one thing, it seems to show that a horrified, engaged center increasingly countering polarization is not a statistical reality. The centrists who haven’t ceded the field yet are using a much shorter lever to pry up a much larger load. What if the center had stayed the same size, and the partisans had just migrated further right or left from quartiles 2 and 4? That’s perhaps the more intuitive migration for those like me who might’ve expected to see signs of centrists and mild partisans who double down as an offset to increasingly bizarre extremist shenanigans. The contrast between that scenario and the actual result is important. We would’ve been getting much more traction with No Labels, NCDD, asteroids, Living Room, transpartisans, and the like.

I don’t think this view countervails your point. I’m with you in that I see much of the way as clear, and I believe the numbers are there if and when we pull up our socks and get out the door together. But I must say that, countervailing the great, wonderful work being done in science and activism on moderation, I have several rats’ nests of anecdotes that illustrate how confused, timid, and unenthusiastic many moderates and moderate partisans have become about fervent and creative compromise. In terms of strategic planning and priority-setting, that dynamic of the center quintile is a discouraging but key piece of the mosaic.