Bridging the Divide between Sensitivity to Minorities and Free Speech

While we often study issues related to bridging divisions between liberals and conservatives, there are many issues that aren’t quite as clear cut. We recently studied an event put on by The Village Square concerning the tension between sensitivity to minorities on campus, which sometimes involve limits on what people can express, versus the principle of free speech. Recent controversies at universities like Claremont Mckenna, Yale, and the University of Missouri have highlighted these tensions, with liberals tending to be more in favor of protecting minorities, but also often pitting liberals against fellow liberals.

At the beginning of the event, the liberal leaning audience was indeed more implicitly inclined toward people who want to err on the side of sensitivity toward minorities, feeling that such people were more likely to be good people who they would want to be friends with. Knowing this, the organizers of the event were able to recruit a free speech advocate who argued their point from a liberal perspective. From the Village Square’s description of their event.

For our Free Speech program we started with a liberal local Rabbi as facilitator who had a very positive relationship with an African American community leader who is beloved locally – and who until recently was a Republican. We knew that Mr. Hobbs had some empathy for both the need to protect minorities and the value of free speech. To complete the panel, we invited Jonathan Rauch of Brookings Institute, who saw the danger of the anti-free speech trends on campus earlier than anyone, originally publishing “Kindly Inquisitors: The New Attacks on Free Thought” in 1993. Rauch argues that the protection of free speech actually protects and advances the cause of minority students – so he makes a liberal argument for a more classically conservative value. Another quality we liked for our panel is that he’s Jewish, so it gave him something deeply in common with our facilitator (to balance the existing positive relationship between the facilitator and Mr. Hobbs). This very high level of pre-existing empathy and cross-cutting relationships made this program quite easy compared to our usual programs, as well as especially enjoyable – though lacked as much tension as some programs do.

We always arrange a meeting between panelists ahead of the program. This gives them the opportunity to break bread together and bond as human beings, by the time they’re on stage they feel to all like friends. As we met for breakfast the morning of the program, when one panelist shushed me up because he wanted to hear more details from the other panelists about something, I sat back and said to our facilitator “my work here is done.” We call this whole process leading up to whoever is on our stage as choreography. We think it is central in delivering results. By the time the program begins, much of the fate of the program is “baked in.” In fact, one could reverse these principles to engineer a disaster, or pay no attention to them and throw the results out to luck.

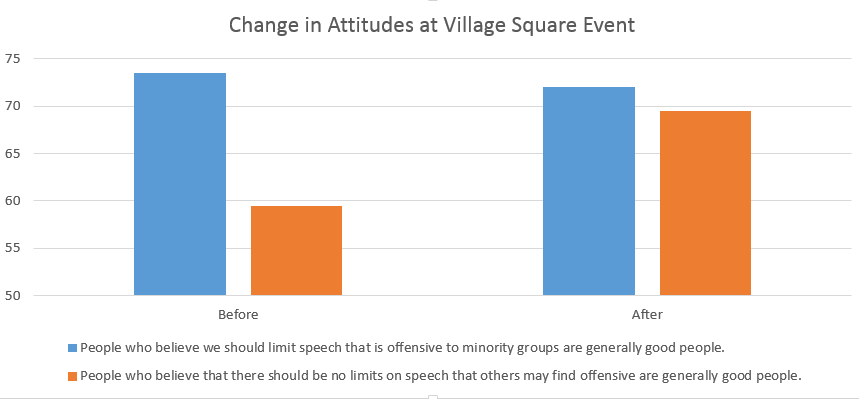

Following exposure to Mr. Rauch and the generally friendly discussion between people on opposite sides of the issue, the liberal audience’s opinions about those who emphasize free speech rose to be comparable to opinions about those who emphasize sensitivity to minorities (see the below graph for a pre vs post event comparison).

As we have found in previous studies of events, there was little change in people’s attitudes about the issue. The generally liberal audience did not feel any differently about protecting minorities or free speech. However, they did feel differently about those who they may disagree with. It is this difference that enables people who disagree about issues to work together, and if we can get more friendly conversations across this divide, and get people out of their moral communities, then perhaps we can avoid a repeat of some of the ugly scenes we have seen on college campuses between two groups of people who both have genuinely good intentions.

– Ravi Iyer

There is, of course, a particular point to me made about a particular person — Sarah Palin — and her response to these questions. It was Sarah Palin's repeated and insistent use of violent imagery in political speech that Congresswoman Giffords had specifically cited as the kind of speech that represents a possible threat to public safety. Congresswoman Giffords herself appeared in the cross hairs of a gun sight on a graphic that was nationally publicized. At this point in time, in the immediate aftermath of the tragedy, Congresswoman Giffords has no ability to reiterate her argument. Shouldn't these events compel the rest of us to at least take another look at it? Don't we owe her that much?

There is, of course, a particular point to me made about a particular person — Sarah Palin — and her response to these questions. It was Sarah Palin's repeated and insistent use of violent imagery in political speech that Congresswoman Giffords had specifically cited as the kind of speech that represents a possible threat to public safety. Congresswoman Giffords herself appeared in the cross hairs of a gun sight on a graphic that was nationally publicized. At this point in time, in the immediate aftermath of the tragedy, Congresswoman Giffords has no ability to reiterate her argument. Shouldn't these events compel the rest of us to at least take another look at it? Don't we owe her that much?