Bridging the Divide Between Religious Liberty and Marriage Equality

I was recently invited to a small gathering of individuals on both sides of the marriage equality vs. religious liberty debate. These issues aren’t necessarily inter-twined, but there have been several high profile cases where homosexuals who were getting married and wanted to be treated equally by businesses in their community have run into business owners who feel that it is a violation of their religious freedom to be forced to facilitate gay marriages. This divide, between those who advocate for marriage equality and those who advocate for religious freedom, has been at the center of numerous recent state law controversies, with the governor of Georgia vetoing legislation that would have emphasized religious freedom while states like Mississippi and Indiana having passed such legislation.

The takeaway I got from the meeting was that the debate need not be so polarized, and that when good people on both sides of the debate are put into the same room (and there are good people on both sides), they naturally become sensitive to the sincere concerns of others about how they felt in being denied service or having their faith-based motives questioned. There are many advocates of gay marriage who care deeply about faith and want to be respectful of those who are religious. And there are many advocates of religious freedom who care deeply about the feelings of homosexuals. As is suggested in our research, when the debate becomes less about abstract policies and more about finding a way to compromise with people you have spent time with and gotten to know at a personal level, common ground is possible.

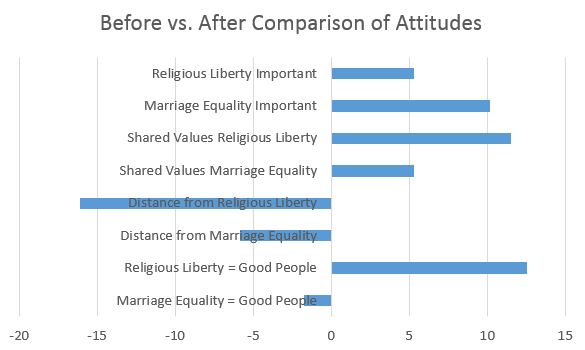

This was certainly our experience of the event, but we also have data to this effect. We were lucky enough to have been invited to survey participants about their feelings before and after the event, concerning people who they agreed with or disagreed with in the context of this debate. The below chart shows change in agreement to various statements, with positive values indicating more agreement after the event and negative values indicating less agreement. As you can see in the chart below, after the event, people came away feeling that both issues were more important, that they shared values more with people of the other side, and that they felt less social distance (more willingness to be friends) toward both groups. There was also more feeling that religious liberty advocates tend to be good people, though little change in attitudes toward advocates of gay marriage, as participants actually came in with surprisingly consistently positive attitudes toward this group already, leaving little room for improvement. That could be something more general or something specific to this group that was willing to meet, which perhaps did not include the most extreme individuals in each camp. Still, overall, while the sample size is not big enough for a traditional academic study, there was certainly a self-reported shift amongst a number of people as a result of such a meeting, which was also echoed explicitly by comments by people in the room after the event..

“Good People” indicates agreement that people who XXX are good people. “Distance From” indicates agreement that If I found out that a coworker was XXX, I would be less likely to be friends with them. “Important” indicates agreement that XXX is an important issue that we should work together to address. “Shared Values” indicates agreement that people who are XXX have many of the same values as I do.

Our experience of this event dovetails well with what most people know as common sense. Rarely are people convinced by facts as to the error of their opinions. There are good people on both sides of the gay marriage/religious liberty debate and they would do well to get to know each other better, as when people on opposite sides get to know each other first, they produce less polarization….and the potential for policies that respect both groups.

– Ravi Iyer