In Going to Extremes: How Like Minds Unite and Divide, Cass Sunstein reviews the social scientific research documenting how people polarize and become increasingly extreme in their views. The process of polarization is often triggered when people are in groups of like-minded others and have little exposure to alternative views. When these groups are isolated from mainstream society and feel marginalized, they tend to share grievances, leading to further radicalization. It is when these conditions are met that polarization can take a dangerous, sometimes lethal, turn. Sunstein argues that one way to reduce this most extreme, dangerous form of polarization is by providing a “safe space” where people feel comfortable discussing their views that is not insulated from divergent perspectives.

Application to Civil Politics

Sunstein’s book explains that extremism and polarization are natural human phenomena to be expected under certain circumstances. In Going to Extremes, he points to a shortcoming of the “deliberative democracy” movement which brings group of diverse citizens together to discuss issues. Some researchers have shown that this strategy of forcing cross-cutting political communications may activate a “tribal” mindset where people are motivated to use their reasoning abilities to support their beliefs and pick apart alternative beliefs. Hugo Mercier and Helene Landemore (2010) suggest that “reasoning is for arguing” and that when people engage in public deliberations, they are particularly likely to exhibit a strong confirmation bias.

Segregation is an important prerequisite for polarization. Bill Bishop’s research (see Lauren Howe’s excellent review here) documents that liberals are tending to live in liberal communities and conservatives are tending to live in conservative communities. With this domestic political migration into ideologically-homogeneous communities, it is no surprise that politically-active Americans are rather polarized today (or, perceive that they are more polarized today; see Fiorina & Abrams, 2009).

Detailed Chapter Summaries

Chapter 1: Polarization

Generally, when people find themselves in groups of like-minded others, they tend to become more extreme in the views which they share with those around them. Simple laboratory experiments have shown that people arbitrarily assigned to sit with people they think share their views exhibit this polarization effect, where they become more extreme in their views on whatever it is that researchers tell them they share in common. When this occurs in the real-world and the point of division is of the sacred moral values variety, polarization is even more profound and may carry with it many negative consequences for the functioning of the disagreeing groups. This shift towards extremity may be accentuated when there are authorities reaffirming people’s beliefs and confirming their biases.

Intuition leads many people to think that groups may become less extreme and less polarized if they can discuss the issues with each other. Rather, deliberation often leads people to taking more extreme positions.

Chapter 2: Extremism: Why and When

Sunstein argues that the way people within groups obtain and share information is one of the essential ingredients for polarization, and likely extremism, too. Generally, what people know is already skewed in a certain direction and when they speak with each other they basically confirm what each of them already believes. Consider Marc Sageman’s research on the radicalization process for terrorists. He finds that, “a group of guys in an echo chamber communicate with each other spiraling to a further extreme until they are moved to join a terrorist group.” Many members of terrorist organizations explain that they joined because of political goals that they have and believe they can best achieve through joining these organizations.

In obtaining information through social networks that are ideologically homogeneous, people tend to assimilate information that leads them to a desirable conclusion. For example, one Pew Poll found that while 93% of Americans believe that Arab terrorists perpetrated the 9/11 attacks, only 11% of Kuwaitis believe this. One explanation is that people in Kuwait are isolated from the United States, receive a particular source of information, and are motivated to view the “enemies of America” as very distinct from themselves.

A similar pattern can be seen in politics in America. People tend to view websites, read newspapers and blogs, listen to radio shows, and watch television programs that support their pre-existing views.

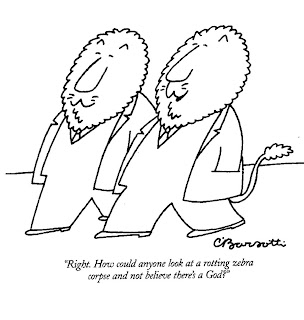

Social psychological research shows that people are biased in how they assimilate information. When presented with the same set of facts and each side’s argument in favor of or against capital punishment, the participants tended to only believe the facts that supported their views and while they tended to discredit the facts supporting the other views. Often, when encountering information challenging pre-existing beliefs, people respond by labeling the uncongenial points as silly or stupid, and derogate the people espousing those points. This can be viewed as “tribalism,” where people rally to defend their tribe and attack other tribes.

Sunstein also notes that political extremists are typically far from irrational. Rather, they tend to have a very narrow set of knowledge on an issue, and what they know supports their extremism. It’s also important to recognize that extremism is not necessarily bad. In fact, extremism is sometimes defensible and right (e.g., Martin Luther King, Jr., Nelson Mandela).

Chapter 3: Movements

Groups that live in isolated communities are more prone to polarization, as they are more likely to have shared concerns, shared grievances, and a shared identity. However, if a group is diffused within the general population, they have less opportunity for discussion with like-minded others and, thus, lack a polarized group consciousness. Successful reform movements often occur because of these processes of polarization, as being in like-minded groups makes it easier to organize and mobilize.

Extremists do not usually suffer from a mental illness. Nor are they typically irrational. Rather, they likely do not have personal and/or direct information about an issue in question. In these cases, people will often rely on what other people think—especially people they view as reliable sources of information. Thus, people who believe in conspiracy theories like the idea that the Central Intelligence Agency was behind the Kennedy assassination (or, perhaps, the view that President Obama was not born in America, or may be the “anti-Christ”) are acting rationally using the limited information they have.

Furthermore, once people hold a certain belief, they are motivated to confirm that belief by accepting confirmatory data while rejecting any disconfirming data (possibly, by saying that it was gathered through bad science, or was being espoused by someone with a political bias).

People tend to feel an “unrealistic optimism” and extremists tend to have the highest levels of unrealistic optimism. In other words, extremists tend to have an inflated perception that their actions will lead to the desired results. If we think of extremists as irrational, it becomes more difficult to understand and prevent their actions. Therefore, it’s important for us to recognize that polarization and demonization are products of basic human psychology which affects most people at some point in their lives.

Chapter 4: Preventing Extremism

Sunstein proposes that there are three primary means that nations typically use to combat “unjustified extremism.”

1) Edmund Burke argued that following tradition provides stability for a society, and, in doing so, protects a country’s citizens from the changes advocated by groups of people stirred by passions of the day. He viewed tradition as a check on extreme movements, as respecting tradition may encourage people to be wary of radical ideas that challenge the status quo. Thus, people who have a high respect for tradition may be the least likely to polarize. Many political philosophers have taken issue with this traditionalist model arguing that tradition is not necessarily good, or inherently better than modern reforms. James Madison famously argued against traditionalism in stating, “Is it not the glory of the people of America that, whilst they have paid a decent regard to the opinions of former times and other nations, they have not suffered a blind veneration for antiquity, for customs, or for names, to overrule the suggestions of their own good sense?”

2) Jeremy Bentham proposed that careful consideration of the consequences of actions can stifle “bad extremism.” A problem with this consequentialist viewpoint is that people tend to selectively interpret evidence and can reach opposing conclusions from the same information. The process of deliberating on these facts with others may lead the groups to become more polarized than they were initially.

3) The third, often associated with James Madison, is checks and balances. The founding fathers of the United States’ constitution had extremism and polarization in mind when developing the system of checks and balances. Specifically, the founders expected the House of Representatives to be a more mercurial branch of government that would craft policy guided most by the popular passions and group polarization. The Senate, however, was to ensure that ill-considered legislation did not become law.

Importantly, group deliberation does NOT necessarily lead to truth. The Jury Theorem suggests that large groups of people can make better decisions than smaller groups, IF the people deliberating in the groups are more likely to be right than wrong. If people the people in the group are more likely to be wrong than right, then the likelihood that the group’s majority will decide correctly drops to zero as the group size increases. Thus, group deliberation is more likely to work well if the deliberators are cognitively diverse (i.e., having different approaches, training, and perspectives).

Chapter 5: Good Extremism

Barry Goldwater was correct in stating that “extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice.” Extremism is not always bad. Thomas Jefferson even wrote that social “turbulence can be productive of good. It prevents the degeneracy of government, and nourishes a general attention to… public affairs. I hold… that a little rebellion now and then is a good thing.” In addition to maintaining the legitimacy of the government, extremism and polarization can promote political engagement and lead to greater political participation.

The problem is not simply polarization, rather it is when people are isolated and have minimal contact with others who have alternative viewpoints. This isolation and the feeling of marginality are the factors that make polarization particularly dangerous. To prevent this type of polarization, Sunstein argues for the creation of spaces where people can discuss their views that is not insulated from those outside of the group (perhaps groups such as The Village Square are doing this).

About The Author

Cass Sunstein is an American legal scholar, former professor at the University of Chicago Law School, and current professor at Harvard Law School, in addition to serving as President Obama’s Administrator of the White House Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs. He has authored 36 books on law, decision-making, and politics. One of his books, Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness, was named “Best Book of The Year” in 2008 by The Economist.