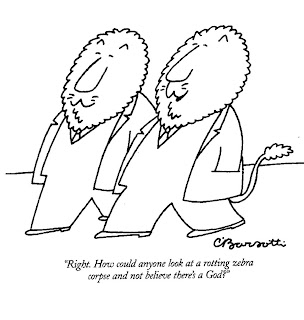

If you don’t agree with me there is something wrong with you: An introduction to naive realism

Ever notice that anyone going slower than you is an idiot, and everyone going faster than you is a maniac?

Is it possible that people driving slower than us are actually idiots and that people driving faster than us are maniacs? Absolutely. Is it possible that we are idiots for driving faster or slower than them? Absolutely… although our brains seem to steer us toward the assumption that we are right and other people acting or thinking differently from us are the deviants.

This phenomenon is called "naive realism." As naive realists, we tend to think that we see events, people, and the world as they really are, free from any distortion due to self-interest, dogma, or ideology. We also tend to assume that other fair-minded people will share our views, as long as they have the same information as I do (also known as the "truth") and that they process that information in the objective, open-minded fashion that we did. Lastly, we generate three possible explanations for why other people might not share our views:

- They haven't been told the truth.

- They are too lazy or stupid to reach correct interpretations and conclusions, or

- They are biased by their self-interest, dogma, or ideology.

An important and related phenomenon is the "false consensus effect." Here, we see that people tend to assume that the decisions that they make are the ones most people would make and that these are the morally-right decisions to make. Because these are the "normal" decisions to make, these decisions reveal less about our idiosyncrasies and individual values. When people make different decisions or take different positions, we assume that it is because of their character and their values (or lack thereof).

Naive realism and false consensus effects are barriers to civil political dialogue and they provide a lens through which we can better understand why liberals and conservatives seem incapable of communicating with one another without calling each other names or assuming that the other side is evil (Hitler-like, the Anti-Christ, or subhuman).

It is difficult to surmount these seemingly basic human tendencies, and we may not even want to overcome all of them. Vigorous debate and intragroup disagreement is healthy for democracy. Thinking that our views are correct and assuming others would share our views likely serve to promote our defense of our ideals and our preferred policies. The problem, though, emerges when disagreement devolves to demonization. Understanding how to prevent this shift is the central goal of my colleagues and friends at CivilPolitics.org, and the most reliable method to minimize demonization seems to reside in promoting relationships between individuals who disagree. In previous generations, where demonization was less rampant, our elected officials spent time with one another outside of work, interacted with each others' families, and knew each other as people, and not just partisan adversaries. Calling someone evil and a liar is much more difficult and unlikely if you know you must face that person's spouse and children later that night over the dinner table.

So, as you are having discussions with people who hold beliefs different from your own and you are trying to enlighten them with "truth," think about whether you could face that person's family over the dinner table after making your argument. If not, you may want to reconsider your argument and think about whether you're being a dogmatic naive realist.