New Research Supports Age Old Ideas for Civility

I recently attended the 2015 meeting for the Society of Personality and Social Psychology, which is the main gathering for academic social psychologists. Here, psychologists gather to share their latest and greatest new research. My goal was to find as much research as possible that may be of interest to our Civil Politics readers (e.g. research relating to bringing together groups across moral divisions in their community).

The meeting can be rather overwhelming as there are hundreds of panelists and thousands of posters competing for your attention, each of which may contain several novel research studies. One of my favorite sessions from this year was a panel entitled: “Finding Patterns in a Maze of Data” and emphasized that “Robust discoveries require the recognition of clear patterns that exist across a wide range of data. By finding these patterns, researchers can construct integrative theories that capture broad fundamental truths.” (full program here) While there may be thousands of potential findings to report, they are all often different takes on the same themes and it is in this convergence, across methods, samples, and research groups, that lends credence to any research discovery. At Civil Politics, we use this same method to gather evidence for our recommendations across existing research, new research, evidence and experience from practitioners, and patterns in the news, with convergence leading to greater confidence that improved interpersonal relationships and emphasizing cooperation over competition are indeed robust evidence-based recommendations. Accordingly, below are a number of new research findings that support and provide nuance as to our existing recommendations, as well as findings that suggest new potential recommendations.

Improving interpersonal relationships

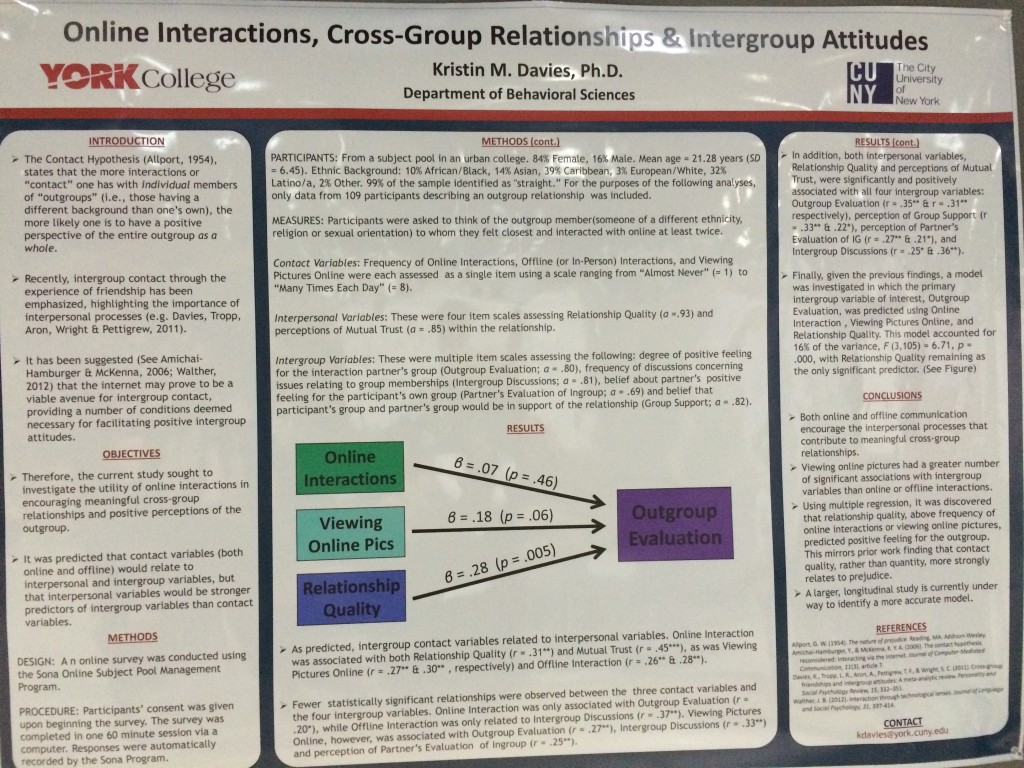

The contact hypothesis, which posits that interpersonal contact under the right conditions can reduce intergroup tensions, was developed 60 years ago, but research continues to this day. For example, this poster by Kristin Davies of York College, showed how contact can extend to the online world, such that online interactions, especially high quality interactions, with members of outgroups was associated with positive feelings toward those groups.

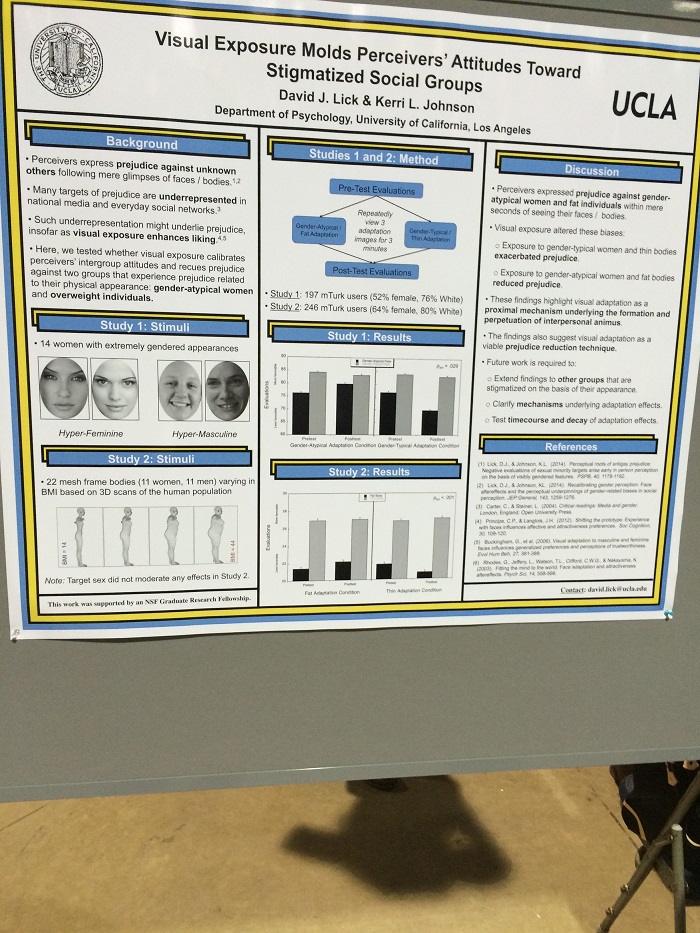

The above poster is correlational, so there are many explanations for the relationships found, but when put in context with all the other research on the contact effect, both at this conference and in the literature more broadly, the patterns are quite clear that positive contact can indeed improve inter-group relations. Another poster from researchers at UCLA used an experimental paradigm and showed a similar effect using a different target group (gender-atypical or overweight individuals), with visual exposure to these groups reducing prejudice.

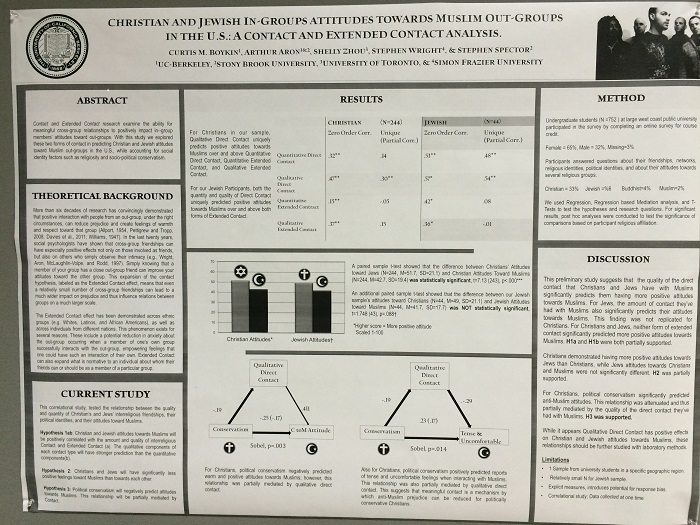

A related study led by Curtis Boykin at UC Berkeley, shows how surveys of people of different religious backgrounds indicates that the quality of interactions with people of other religions may a persons’ attitudes toward people of differing religions.

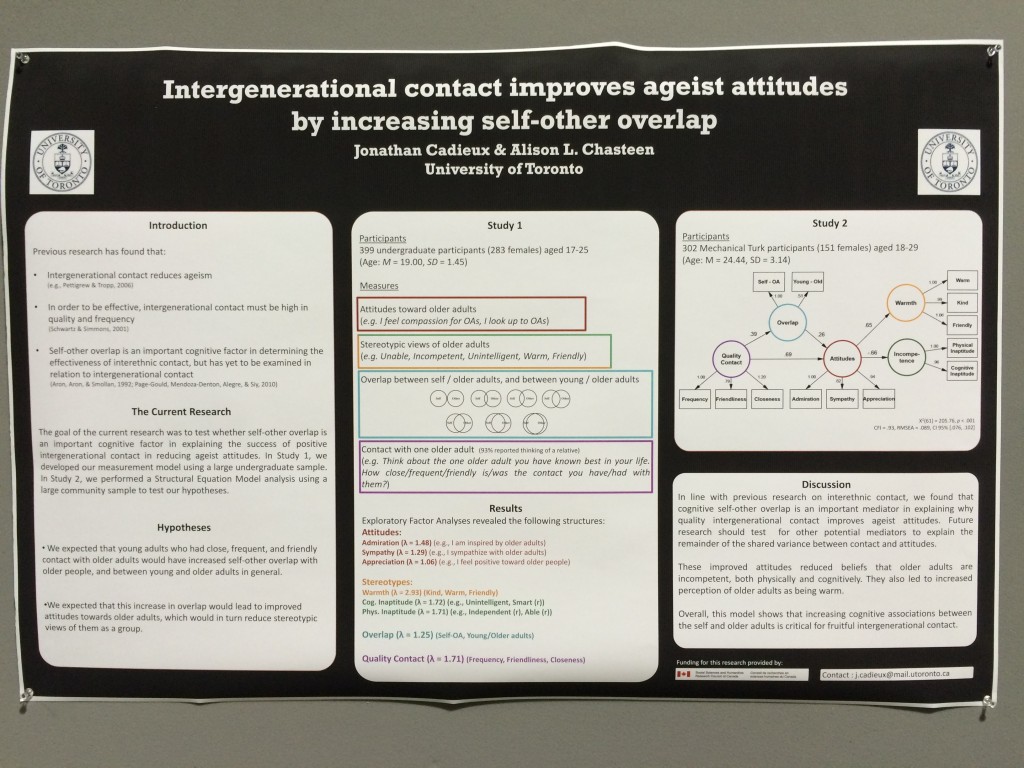

This next poster led by Jonathan Cadieux and Alison Chasteen at the University of Toronto, sought to refine the mechanism whereby quality contact with older individuals led to less ageist attitudes, showing that measures of self-other overlap with older individuals helped explain this decrease.

It’s worth noting that the above studies, all in-line with existing research, used varied samples (students vs workers on Amazon’s Mechanical Turk), methods (surveys vs. experiments), and target groups (by age, race, religion, and body type) and all came to similar conclusions. It is this kind of convergence that gives us confidence in recommending improving cross-group relationships as a means toward bridging inter-group divisions.

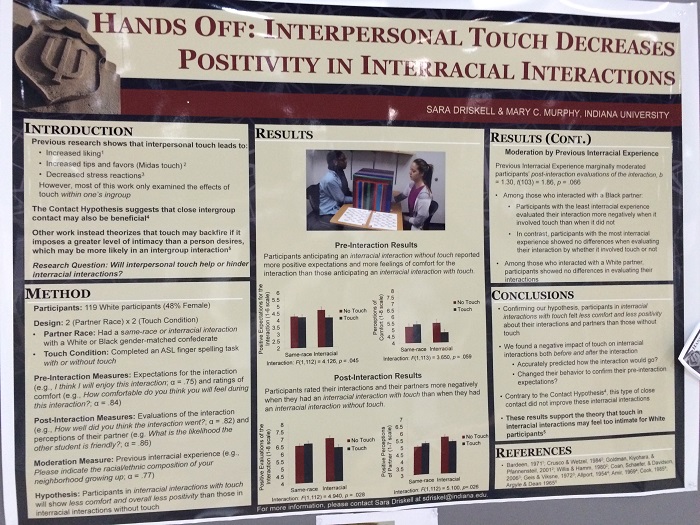

How can we improve cross-group relationships? Mere exposure is not enough and the above studies emphasize the quality of contact across groups, an idea that has been explored previously in the literature as well. For example, the below poster, led by Sara Driskell and Mary Murphy at Indiana University, shows how uncomfortable/negative contact such as being forced to touch a stranger, can actually lead to worse inter-group attitudes.

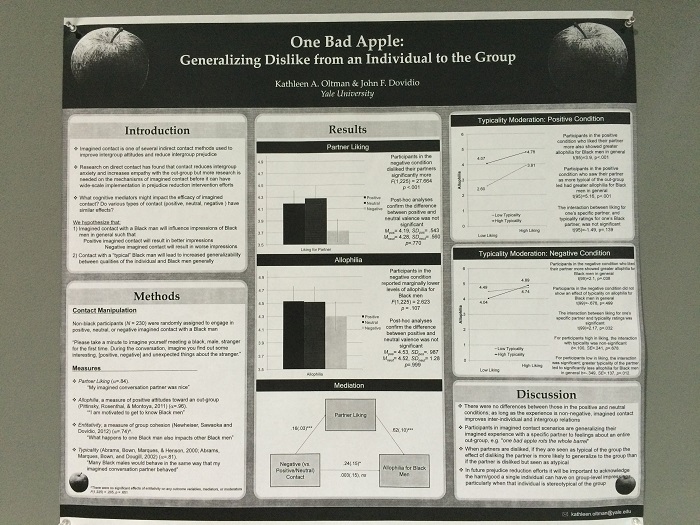

Similarly, this study from Kathleen Oltman at Yale, shows how even imagined negative contact with an individual of another race can lead to more negative attitudes toward the whole group.

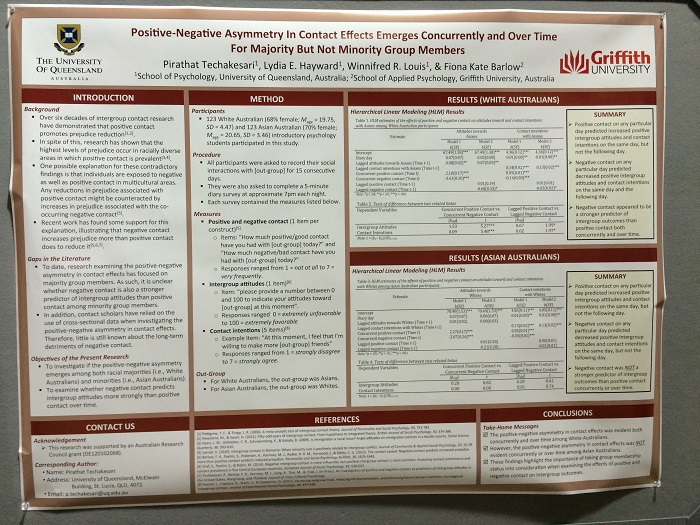

The above study did not find that positive imagined contact had the opposite effect, as the effects from negative imagined experience were greater. This has been found in previous literature, where negative experiences are more impactful than positive experiences, which is something that people bringing groups together should be aware of. The below poster, let by Pirathat Techakesari of the University of Queensland, explores this asymmetry in more detail. In an experience sampling study of attitudes of White vs. Asian Australians, they showed that negative experiences may be more impactful for majority groups, but that this asymmetry was not found for minority groups.

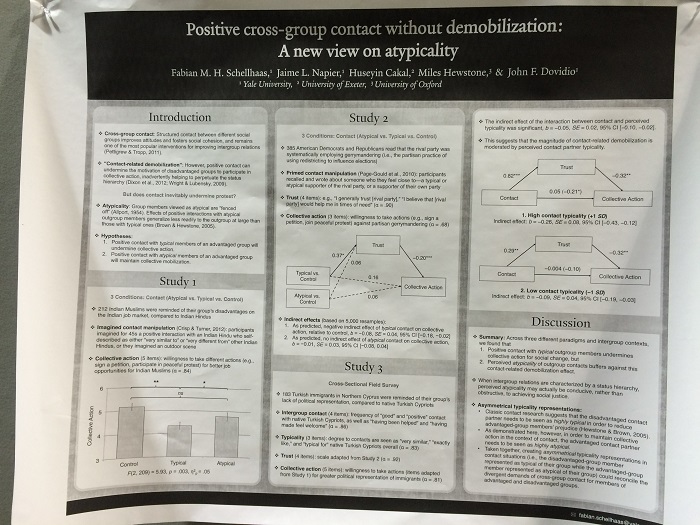

Clearly those seeking to bring groups together should avoid exacerbating differences through negative inter-group experiences. Another potential negative effect that I may not have thought of was presented by Fabian Schellhaas and colleagues, as they expanded on previous research that showed that positive cross-group contact can undermine the desire for disadvantaged groups to mobilize to change the status quo by showing that this happens more when the individuals involved are perceived as typical members of their group.

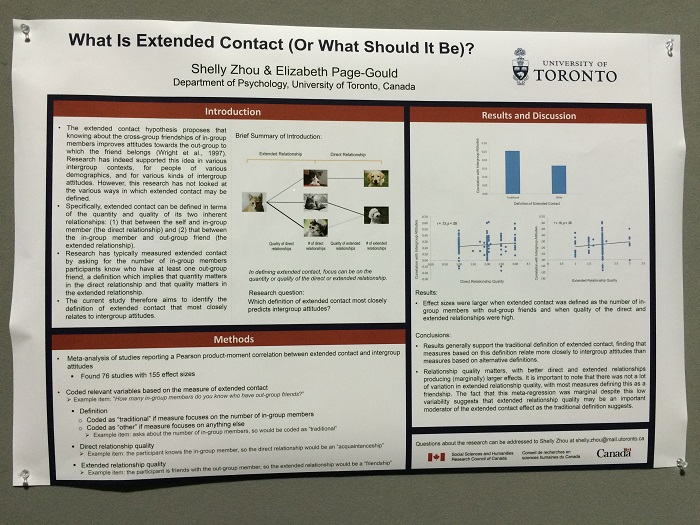

Finally, the below meta-analysis of extended contact effects, which involves a line of research that shows that seeing other people’s inter-group friendships can improve one’s own inter-group attitudes, further emphasizes the importance of relationship quality, as opposed to mere contact.

In summary, while no study is conclusive and all have flaws, including these, there is a great deal of convergent evidence from new research that confirms and expands upon what we already knew from previous research, specifically that positive experiences with members of other groups leads to better inter-group attitudes.

Fostering Cooperation over Competition

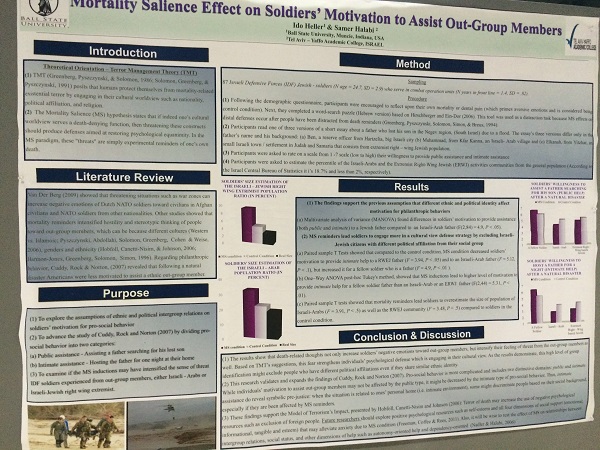

Our second main recommendation for improving cross-group divisions is to foster cooperation over competition. A number of studies at this conference also confirmed and expanded upon previous work in this area. Competition often arises from scarcity, threat, and the resulting competition for limited resources that can stave off these threats. As such, consistent with previous research, reminders of one’s own mortality and the possibility of death are detrimental to inter-group relationships. Here, Israeli soldiers who were reminded of their mortality showed decreased positive attitudes toward Israeli-Arabs.

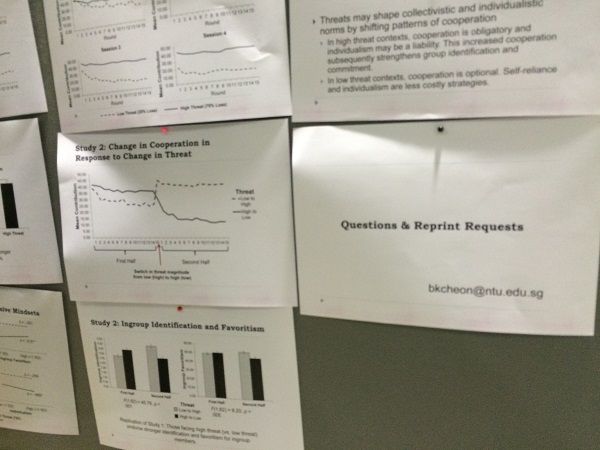

More generally, a simulation using public goods dilemmas, led by Bobby Cheon of Nanyang Technological University, showed how threat can lead to an adaptive response where individuals favor their ingroups over others.

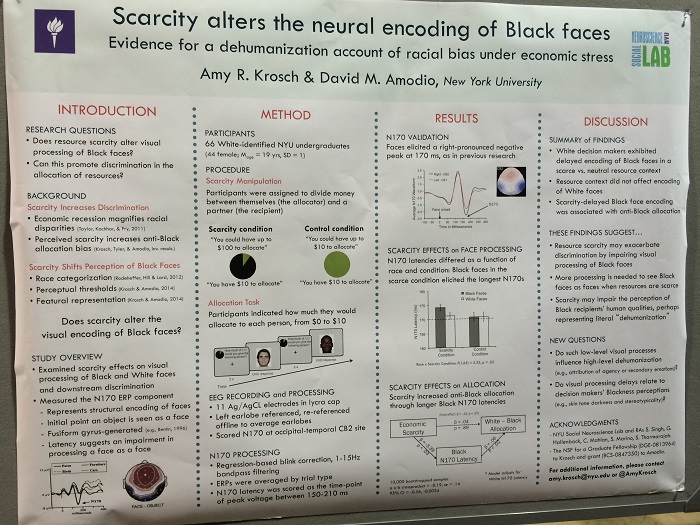

Similarly, the below study led by Amy Krosch at NYU, used psycho-physiological measurements to show that scarcity leads to greater lag in encoding other-race faces, suggesting that this may be a mechanism for the dehumanization that often precedes inter-group tension and violence.

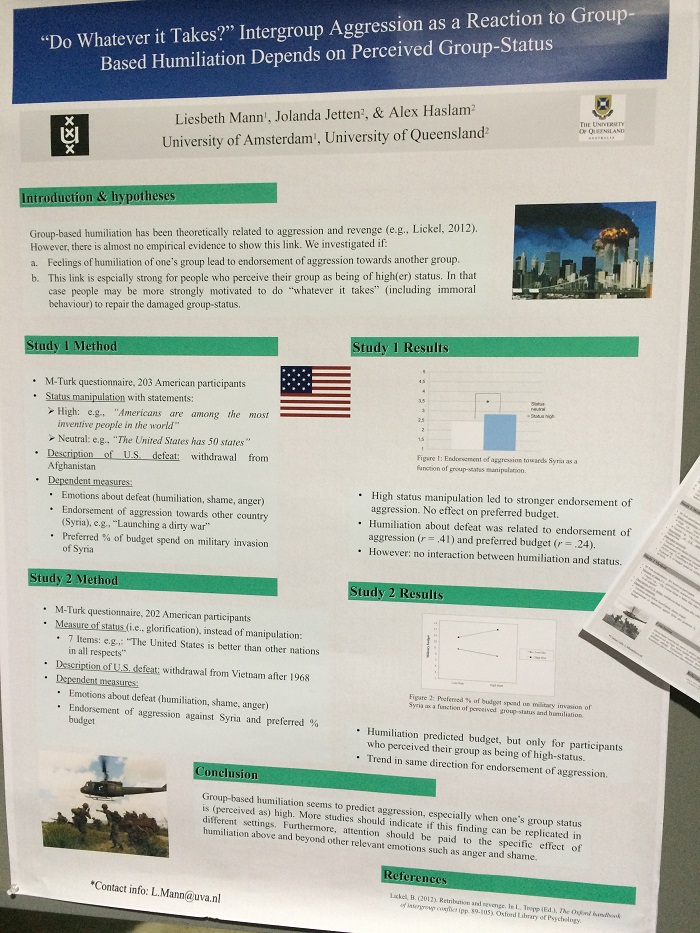

Threat and the competition for limited resources does not have to involve physical goods. Many wars have been started in part due to collective humiliation and the below study led by Liesbeth Mann of the University of Amsterdam, also indicates that group based humiliation can lead to aggression, with the caveat that this may be more true for higher status individuals.

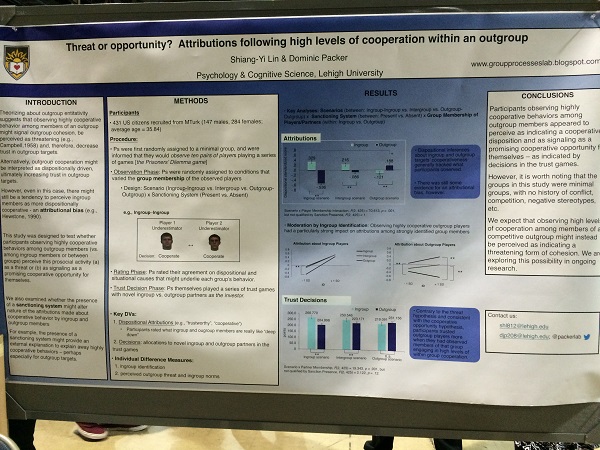

In contrast, in the absence of threat, seeing cooperation amongst those from an out-group actually may lead to a perception of opportunity rather than threat, as this study by Shiang-Yi Lin and Dominic Packer from Lehigh University showed.

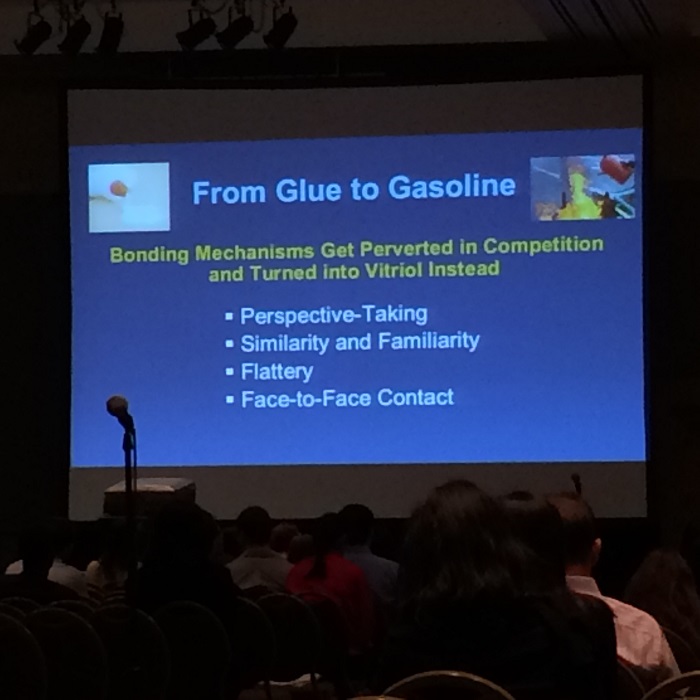

Indeed, the lack of a competitive situation can often change the meaning of many things that would otherwise be perceived as threatening. One interesting talk from the “Finding Patterns in a Maze of Data” symposium by Adam Galinsky at Columbia, showed how competition can lead the same forces that bind us (glue) to fan the flames of conflict (gasoline). Specifically, intergroup contact, similarity, flattery, and perspective-taking can all actually lead to greater conflict in a competitive context, even as they bind people together in cooperative contexts.

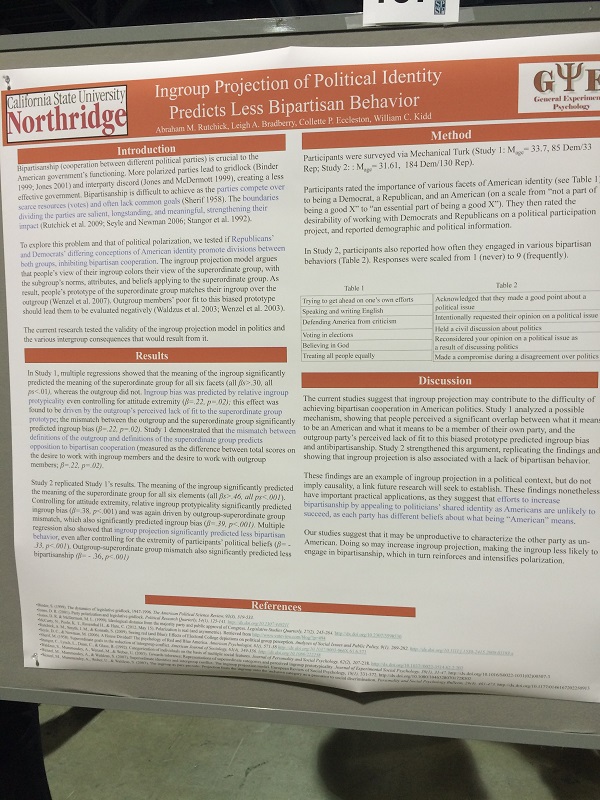

The above research naturally begs the question as to how we get more cooperation and less threat. One method that is often used is to prime a collective goal or identity that can be shared across groups. Consistent with this previous research, the below study led by Abraham Rutchick at Cal-State Northridge, suggests that greater perceptions of a super-ordinate identity (e.g. we are all Americans), leads to more bipartisan behavior.

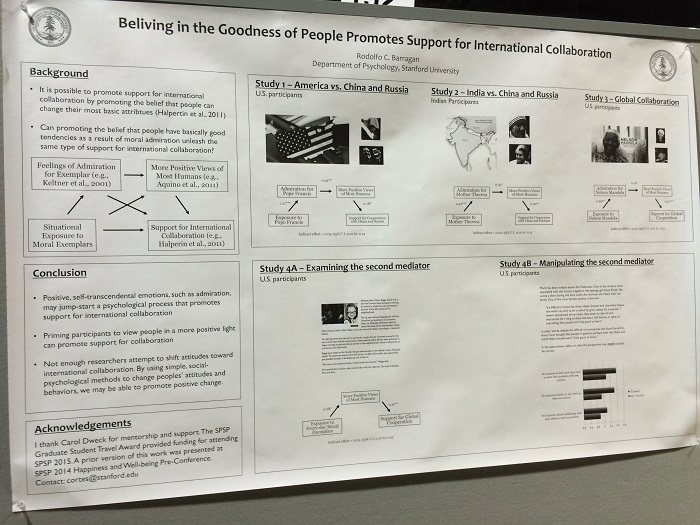

If threat increases competition, and therefore increases intergroup tensions, it stands to reason that situations that reduce threat will increase cooperation. For example, the below study by Rodolfo Barragan of Stanford showed how increasing perceptions of the goodness of others may increase cross-group collaboration, perhaps by instilling a more global superordinate identity.

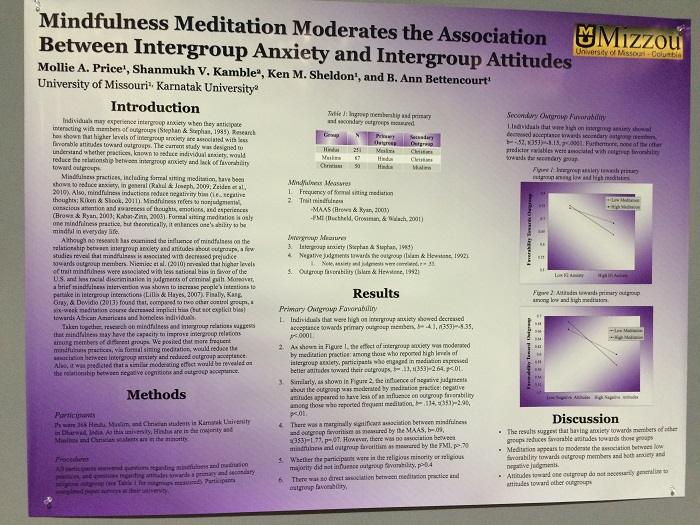

At a more psychological level, the below study led by Mollie Price at the University of Missouri showed how mindfulness may reduce one’s anxiety and threat sensitivity, leading to improved inter-group attitudes.

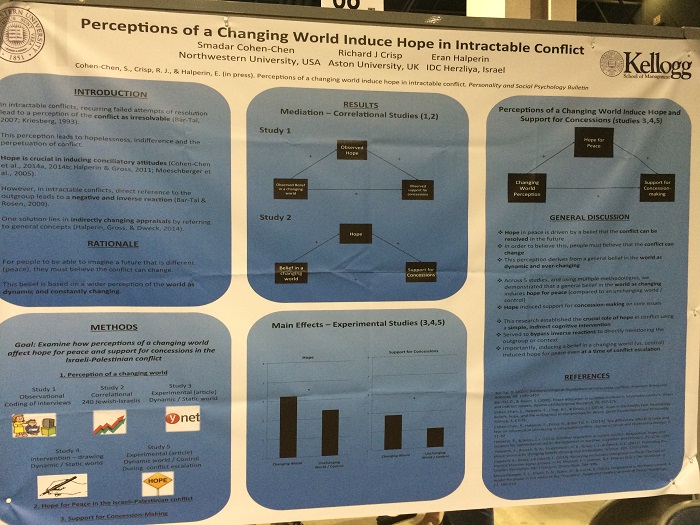

Similarly, feelings of hope, which may be helped by perceptions of a world that is dynamic and changing, can also lead to an improved desire to cross group divisions, as this work led by Smadar Cohen-Chen of Northwestern shows.

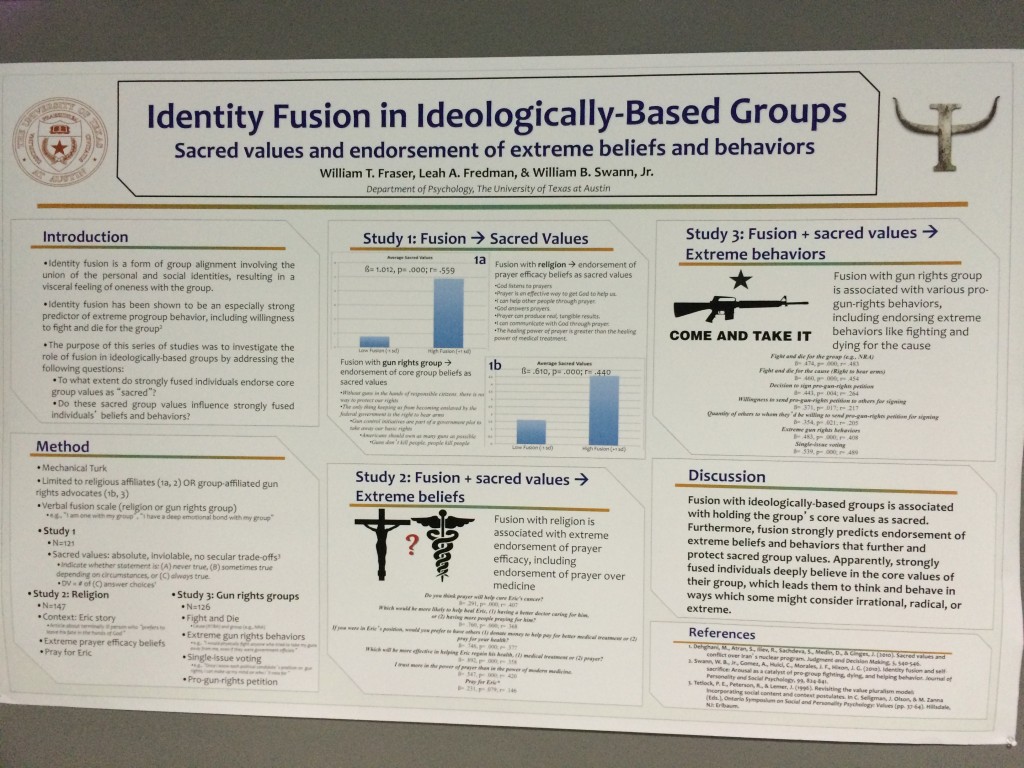

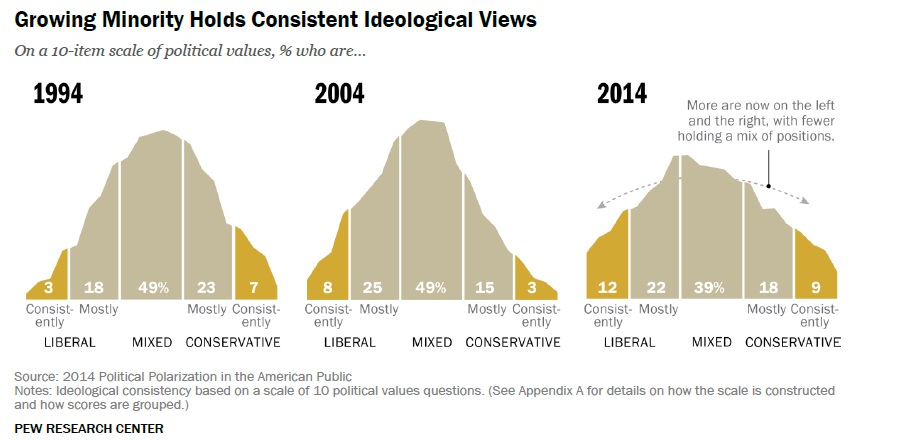

One way that competition ensues is when conflicts become moralized. Here, differences are no longer matters of preference, but take on an existential quality, where the beliefs of another group threaten one’s identity. In the below work we see work led by William Fraser at UT-Austin, on how people who have are fused with ideological groups tend have extreme beliefs and behaviors that may exacerbate inter-group tensions.

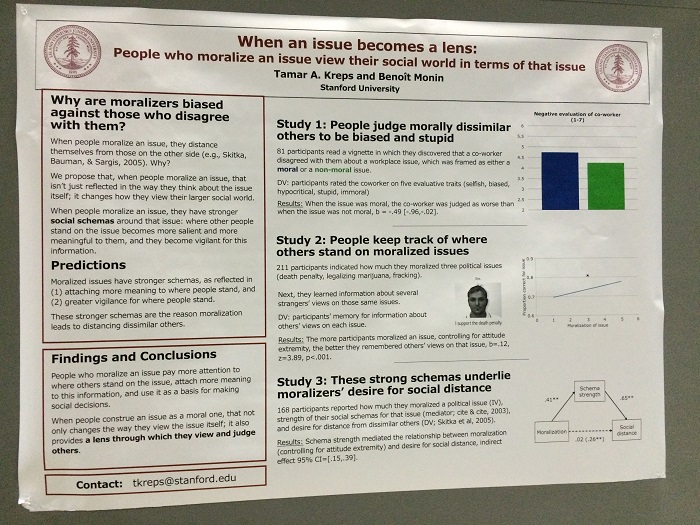

In addition, this study led by Tamar Kreps at Stanford shows how people who moralize an issue may see the world through the lens of that issue, making it harder to bridge intergroup divisions.

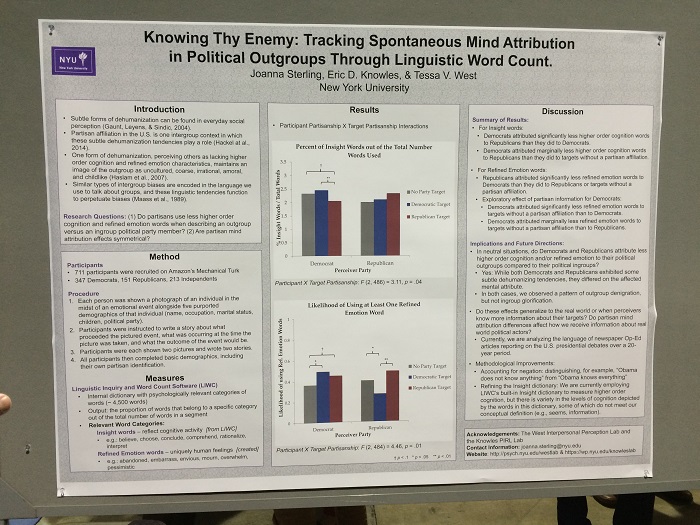

As a result, when we have competitive situations between two morally conflicting groups, we see not just a difference of opinion, but a dehumanization of the other group. In this study led by Joanna Sterling at NYU, we see this dehumanization measured in terms of less higher order cognition attributions to the other side.

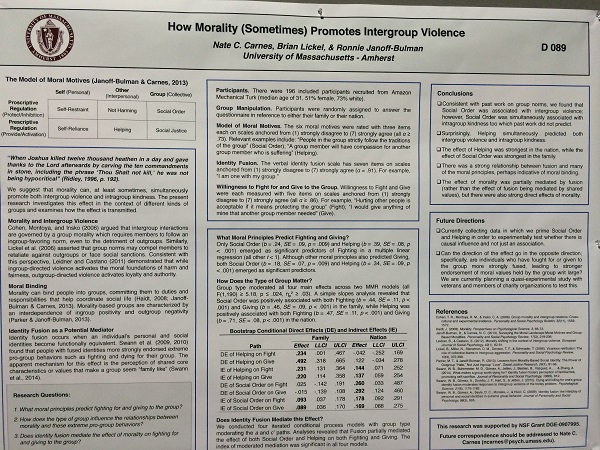

This extremity, singular perspective, and reduced consideration as to the humanity of the out-group can lead to violence. In the below picture, Matt Motyl, professor at University of Illinois and a board member of Civil Politics, is having work by Nate Carnes from UMass-Amherst explained to him. The study shows specifically how moral motives can be associated with endorsement of intergroup violence.

The above recap represents just a percentage of the research presented at SPSP 2015, given that multiple sessions occur at any time. While each year, much new research is presented, a great deal of this research supports old ideas, just in new contexts. For example, while past researchers may have studied race in the context of school integration, these researchers are studying body image in the context of online settings, yet the variables they use – specifically positive experiences with other groups – remain the same. Similarly, the idea that tensions often arise between groups that compete with each other for scarce resources, whether they be a piece of land or jobs or a sports championship, is an old line of research. However, new mechanisms that increase or reduce threat/competition are being explored as there are many avenues toward fostering cooperation between groups. Hopefully this overview of some of the more pertinent new research can both confirm existing ideas that people trying to bring groups together already have and inform some new ideas as well.

– Ravi Iyer