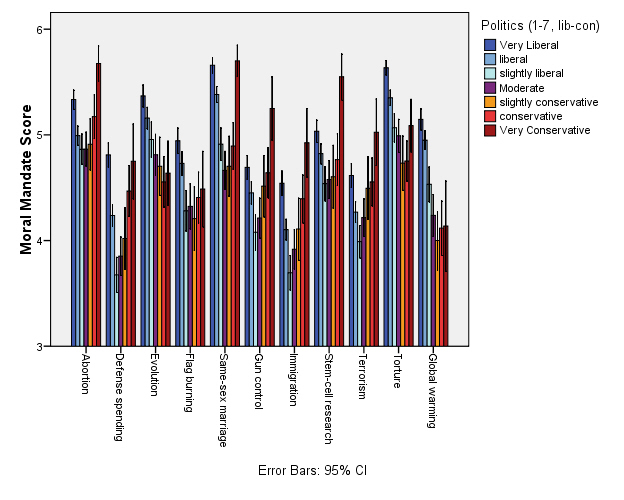

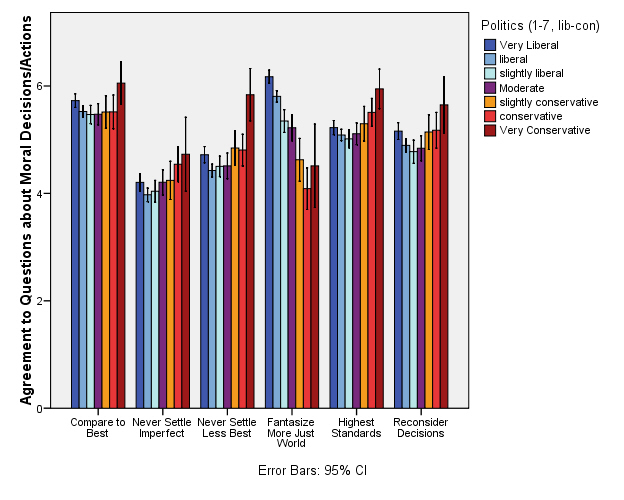

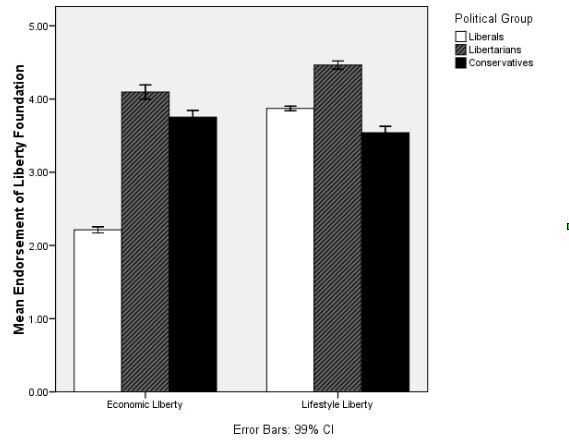

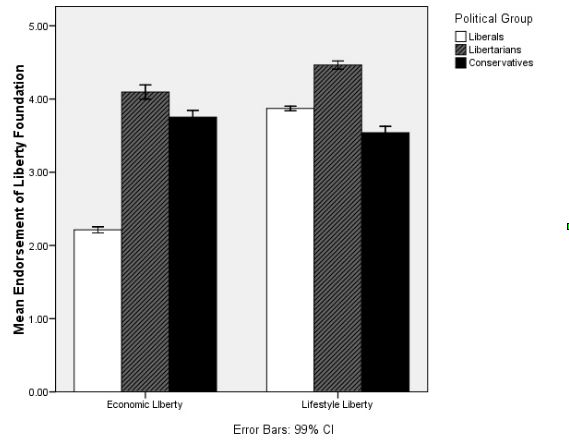

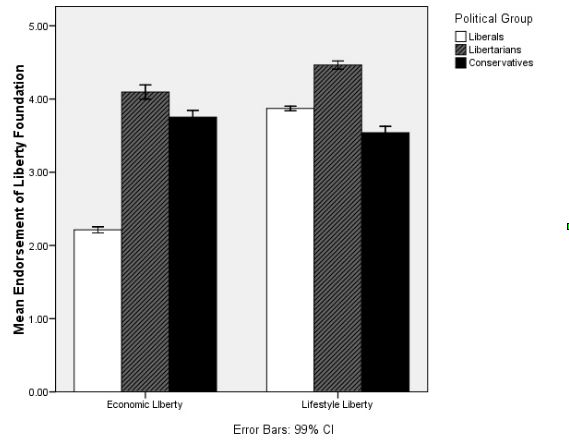

We recently submitted a paper for publication about libertarian morality, along with co-authors Spassena Koleva, Jesse Graham, Pete Ditto, and Jonathan Haidt. The paper leverages our broad set of measures to tell a story about libertarians, which converges with previously reported findings about liberals and conservatives. Specifically, all ideological groups demonstrate the same patterns whereby preferences, emotions and dispositions lead to an attraction to corresponding values and ideological narratives. For example, liberals have greater feelings of empathy and are therefore more likely to moralize harm and be attracted to an ideology which prioritizes this moralization. Libertarians moralize liberty, both economic liberty, similar to conservatives, and lifestyle liberty, similar to liberals.

Libertarians believe in the importance of individual liberty, a belief that may be related to lower levels of agreeableness and higher scores on a measure of psychological reactance (e.g. “regulations trigger a sense of resistance in me”). They moralize concerns about harm less than liberals, in part because they have lower levels of empathy . They moralize principles concerning being a group member (obeying authority and being loyal) less than conservatives in part because they have less attachment to the groups around them.

If you want to read more about what the paper, says, you can click here or download the paper here, but right now, I’d like to focus on why we wrote the paper, as I have previously written about how people are attracted to why you write things as much as what you write.

Of course, some part of paper writing is driven by curiosity and the practical desire to publish. But in writing this paper, I have undergone my own personal intellectual journey, and I’m hopeful that others may have a similar experience. A lot of my impression of libertarianism was previously shaped by images of the Tea Party (who aren’t necessarily libertarians after all) and I thought of libertarians as uncaring, from my liberal perspective, in that they typically don’t support progressive taxes and social programs. The original title of the paper was “the Search for Libertarian Morality”, implying that libertarians are potentially amoral, and in retrospect showing my own ideological bias.

But as I read more about libertarian philosophy and looked more carefully at the data, I found that libertarians do indeed have a coherent moral code, that simply differs from my own. Like my liberal leanings, which have some relation to my dispositions and preferences, libertarians also moralize their preferences and dispositions, in ways that mirror my own processes. For example, liberals and libertarians both score high on desire for new experiences and stimulation, which may be a common reason why both groups tend to emphasize individual choice over group solidarity, compared to conservatives, as cohesive groups can limit choice. Libertarians may be less moved by emotions such as disgust and empathy, which may lead them to moralize certain situations less than others. But who am I to say that my moral compass is any better or worse than theirs, given my view that at some level, the basis for my liberal moral compass is driven by subjective sentiment. I previously wrote about the dangers of liberal moral absolutism, and villainizing libertarians for not sharing my particular vision of morality would be a step down that road.

Why do we seek to publicize this paper? In a time when partisanship dominates, policy suffers, and people on both sides of the aisle villainize the other side, it is our hope that with greater understanding comes greater acceptance. We may not all agree about the relative merits of empathy, disgust, or reactance as moral emotions…but we all have some level of all of these emotions and can respect principles born out of these. Even liberals can find things so disgusting that they are seen as wrong, and conservatives actually give a lot of money to the poor. In attributing moral disagreements to dispositions, largely out of our control, perhaps we can learn to see others as different and attracted to other positive moral principles, rather than amoral and oblivious to the moral principles that are important to us.

– Ravi Iyer