On the Morality of Torture & Utilitarianism

I personally do not believe in torture, but I have to admit that when I think of it, my mind prototypically thinks of the potential harm that might befall an innocent person caught by an unscrupulous policeman who is all too sure of his moral superiority. What would I do if I knew with 100% certainty that torture of a known murderer/rapist would save countless lives, including the lives of many people I knew and loved?

Is support for torture restricted to the evil among us (e.g. liberals who think that Dick Cheney = Darth Vader)? When individuals say that they are torturing an evil few in order to save many innocents (an argument based in Utilitarianism), are they lying about their noble goals? A recent paper in the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology suggests that individuals may not be honest about their utilitarian motives. From the abstract:

The use of harsh interrogation techniques on terrorism suspects is typically justified on utilitarian grounds. The present research suggests, however, that those who support such techniques are fuelled by retributive motives.

This is a very well done experimental study, which illustrates an important point about other potential motives for torture, specifically a desire for retribution or vengeance. However, it may be nitpicking or splitting hairs, but I might instead have written “those who support such techniques may also be fuelled by retributive motives.” Indeed, in the study itself, there is an increase in support for severe interrogation techniques when there is a greater likelihood that the suspect is withholding information that may save lives, especially among Republicans, the group most likely to be “those who support such techniques.” The fact that retributive motives exist, does not necessarily mean that utilitarian motives do not. One could probably design a study that shows the opposite, where utilitarian motives dominate, given the total control one has in a lab environment.

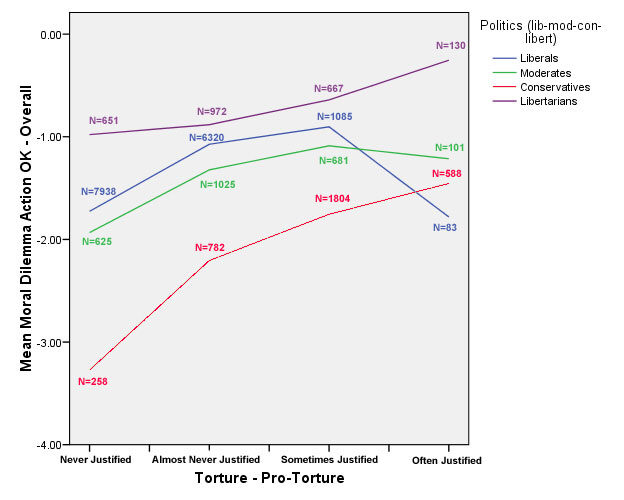

Our yourmorals.org data suggests that utilitarian motives are indeed important in predicting attitudes toward torture. There are a number of measures that tap utilitarian thinking, but the most convincing to me are the classic moral dilemmas that ask people if they are willing to take some action (e.g. flipping a switch) to save 5 innocent people at the cost of 1 innocent life. They are convincing because they are generally free of any political content or judgment about the worth or guilt of individuals. Below is a graph relating responses to these dilemmas to attitudes toward torture. Higher scores on the Y axis indicate more willingness to sacrifice 1 life for 5. Higher scores on the X axis indicate willingness to support torture in more situations.

There is a fairly robust positive correlation between utilitarian judgments on these dilemmas and support for torture (the dip on the far right for liberals is likely due to there being such a small number of liberals who think torture is often justified).

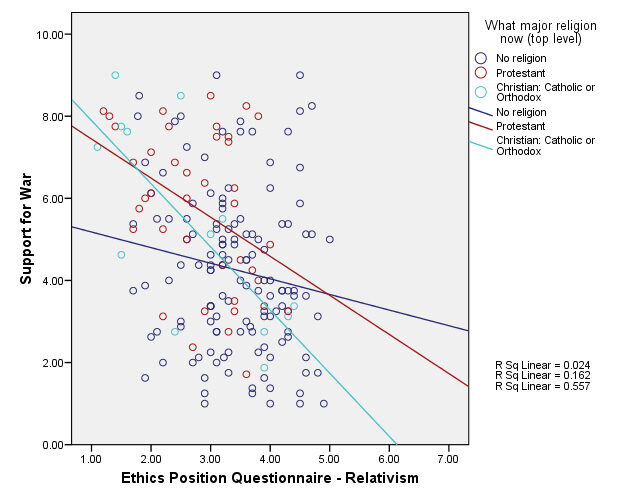

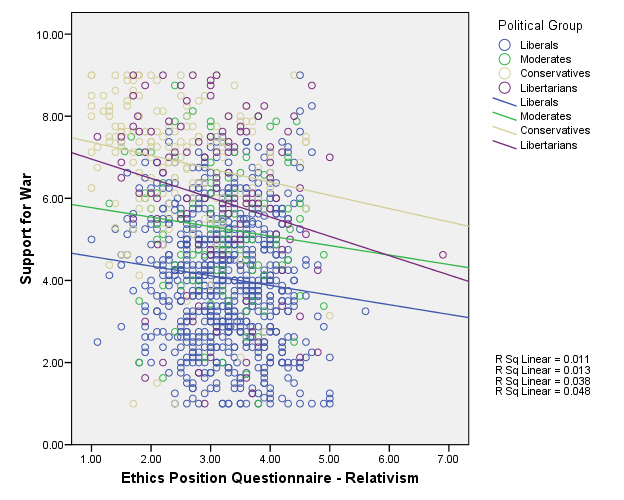

If I look at other utilitarian measures such as moral idealism (using the Ethics Position Questionnaire – e.g. “The existence of potential harm to others is always wrong, irrespective of the benefits to be gained.”, r=-.35) or moral maximizing (using an adapted version of Schwartz’s maximizing-satisficing scale – e.g. “In choosing a moral action, one should never settle for a morallyimperfect action.”, r=-.15), you find the same relationship. Controlling for political affiliation and beliefs about punishment and disposition toward vengeance, one still finds significant relationships between utilitarianism and support for torture.

My take home. Part of promoting civil politics is to take people at their word for their motives, rather than questioning them. There may indeed be some vengeful motive behind torture…but there are utilitarian motives as well and those of us who dislike torture might actually get further confronting torture on utilitarian grounds rather than attempting to question the motives of those who believe in torture.

– Ravi Iyer